JOURNAL

documenting

&

discovering joyful things

Sustainable travel

I’m sorry.

I’m going to apologise to you, first, but then also to the planet. Because the truth is that as much as I tried to be mindful and sustainable while we were travelling as a family last year, I failed more often than I succeeded, and I suspect I could have tried so much harder.

I realise this confession is not very helpful, especially if you happen to have opened this post in the hopes of finding tips for sustainable travel (perhaps we could brainstorm ideas together?). But I think confessions are an important. I fail all too often when it comes to taking care of the world we live in, and I think it’s important to own my failures, and to let myself feel the shame rather than sweep it under the carpet, so that I can do better next time.

Also, maybe if you sometimes feel that everyone else is a zero-waste champion, carrying around a year’s worth of waste in a single mason jar while you forgot to bring the reusable bags to the supermarket last week… my confession might help you feel a little bit better, and perhaps a little less alone. We have a better chance of success if we support one another.

(A bit of context: we were on holidays for one month. There were five of us, three adults and two children, making our way from Dinan in France to Scotland, via Paris and London, staying in Air BnB homes along the way. Our time in the village hadn’t been a brilliant success at sustainability (I shared some of our experiences and ideas here), but it turns out that life on the road can make things a lot more difficult.)

Things that did work well

First, the positives. There were some things I did that worked really well, making life easy and practical for us on the road while also going a small way towards minimising our footprint. They included:

We used public transport as much as possible. From the time we left Australia in August to our return at the New Year, we took trains and buses almost everywhere. We only hired a car for one week, in order to travel in the Scottish highlands, and only took a taxi on one late night in London, and two extremely early (one of them 4am) mornings

I packed three beeswax wraps of varying sizes when we left for our trip, and used them to cover just about anything. They were especially useful in Dinan, but also came in handy when, for example, we wanted to transport a half-eaten cucumber from one Air BnB home to another, without using plastic wrap or take-away plastic boxes

I had also packed a square, collapsible, insulated lunch bag. Again, back in Dinan this was great for carrying cold things home from the market, but it was also handy once we hit the road, not only carrying food from the shops but also storing it and taking it with us from one place to another, rather than throwing things away

I bought some tourist-style biscuit tins. I love to use tins at home for storage, but they were also very helpful while we were travelling, slotting and stacking neatly in my suitcase, and carrying everything from food to stationery supplies to first aid. (Clearly I had already eaten the biscuits. I did it for the planet)

I packed two heat-proof drink-bottles with me when we first left Australia. One was glass and I accidentally smashed it in a ceramic sink in our London B&B, but the other was wood with metal insulation, and is still going strong. I’d fill this with water before leaving from the day, so that we didn’t need to buy plastic bottles of water

I packed two tote bags for carrying groceries, and bought a couple more when I needed them. I also wore a back pack every day (this one), rather than carrying a handbag. It could expand to create a surprisingly big space, and I’ve carried full-sized blankets in it, bottles of milk and wine, stacks of books, and secretly-stashed Christmas presents. Mostly I was pretty good at bringing bags with me, even for things like Christmas shopping. I think we used three or four plastic bags in total in the month we travelled, and those I saved to use as garbage bags in our B&Bs

Things we really should have done better

I didn’t bring a reusable coffee cup. In France, this didn’t matter. I drank tea at home and coffee in cafes and, knowing this would be the case, I just didn’t add it to the luggage I was packing. But in London and Scotland, often my husband would go out early while I was getting the kids dressed, and bring back two coffees and the newspaper to read. It was so nice to have a ‘proper’ latte after all that time that my conscience grew weak.

Lesson: I should have said “no thanks.” Or waited until I could leave, too, and had the coffee in the cafe. I did sometimes, but mostly I didn’t, and I’m sorry.

I took a big bag of soap nuts with me when we first went to Dinan, and used them for several months. But then the ancient washing machine in our rented apartment tore apart the little muslin bag I used for them (as well as several items of my clothing). I didn’t know how to replace it, so I had to buy ordinary laundry powder to use on the road. I tried to find earth-friendly detergent but still ended up with a kind of contact-dermatitis on my legs and torso, which doesn’t bode well for the waters it drained into.

Lesson: I’m not sure. Learn how to sew my own little muslin bags? There’s no way I could have carried a month’s worth of clean clothes for five people travelling in winter. Can you help? What would you have done?

I used traditional Christmas wrapping paper, even though I knew it probably couldn’t be recycled. There was a lot of angst around this (for me) and in the end, I chose paper because a) by the time we arrived in Edinburgh, where we’d be for Christmas, we only had two days left to organise everything, b) I couldn’t find brown paper and didn’t have time to decorate it anyway, c) my husband doesn’t like furoshiki wraps because he thinks they don’t get used, and anyway I couldn’t afford to buy enough for all the presents, d) the children didn’t have Santa stockings or sacks, so I wanted to create some kind of ‘unwrapping’ experience for them, and e) we didn’t have a tree or much in the way of decorations, so the other adults travelling with me quite rightly felt a bit of festivity was in order.

I didn’t want to be the wowser in the group, and perhaps by this point was feeling a bit (or a lot) hypocritical about pushing the issue, given all the other slip-ups and outright failures we’d been making along the way. It’s hard to be vigilant about recyclable wrapping-paper while sipping coffee from your take-away cup.Lesson: In retrospect, the smartest thing would probably have been to bring two stockings or sacks for the kids, so that the Santa presents didn’t need wrapping, and then to use a combination of cloth, tea-towels, ribbons and other ideas for our presents to one another. Also, I’m going to teach myself how to properly use furoshiki wraps, so by next year, my husband might accede to their usefulness.

Food waste and recycling was tricky. I did manage to sort-of minimise our food waste, but we were limited in terms of recycling options, depending on the rules of each home we stayed in. I’ve written before about the challenges of not bringing things in, rather than figuring out what to do with the things on the way out, but I don’t think I was particularly good at this, especially once we hit the road.

Lesson: Really, there’s not a lot you can do in these situations, other than to be mindful of what you bring in, and I just needed to be more vigilant in that respect. It’s a lot harder to cook at home while on holidays, and can sometimes be counter-intuitive (the amount of ‘things’ we’d need to buy for just one meal in terms of food ingredients that wouldn’t get fully eaten, and all the jars, tins and plastic they come in, would possibly be more wasteful than a single take-away pizza box or plastic container), so I guess the answer is to think hard and creatively about what comes in, every time.

Air travel. This is the giant, white elephant in the room when it comes to sustainable travel. Here we are as ‘responsible’ human beings, travelling with our keep-cups and tote bags, while just to get where we want to go, we are participating in an industry that is responsible for more than 2 percent of the entire world’s carbon dioxide emissions by burning finite fossil fuels, emitting greenhouse gases, and leaving contrails in the atmosphere. In addition, airports and the related infrastructure (terminals, runways, ground transport, maintenance facilities and shopping) use up huge amounts of energy, water and resources.

Lesson: Clearly, the easy answer is not to travel by plane. But I am selfish and I do want to travel, at least sometimes. Australia is an island, so any international travel requires flying. It’s a start to participate in a carbon offset scheme (where trees are planted to ‘offset’ the fossil fuels your journey burns). I did this and don’t want to discount it, but to me that feels like a tiny drop in the ocean.

I have had another thought: I’ve read that the per-passenger-per-kilometre carbon emissions of air travel are roughly the same as travelling by car. So now, back home, I need to be even better at not taking our car, walking instead, or using public transport if necessary. (Although to get from Melbourne to Paris, and then to get home from Edinburgh to Melbourne, we flew 33,682 kilometres. Multiplied by the five of us, that’s 168,410 kilometres, so I have a lot of walking and tram-rides to do before I even break even from this one trip, environmentally-speaking. It’s not a perfect system).

What do you do? How do you combine air travel with your environmental conscience? What are your top tips for thoughtful, sustainable travel?

Comfort food

When I was in my early 20s, my then-boyfriend and I used to go and stay with his grandparents, in their little blue weatherboard cottage in the country, beside a lake. I remember waking early in the morning and going for long walks on the sand, watching dolphin families fish for breakfast. Morning tea with his grandma, served precisely at 10am every day, was always tea in a big pot, and Iced Vo-Vo biscuits.

One year, a few days after Christmas, we were less than an hour into our journey back home to Sydney when we received a sad phone-call: my boyfriend’s grandfather had had a heart attack, and died. We immediately turned around and hurried back to the weatherboard house, which by the time we arrived was already overflowing with family-members: parents, sisters, uncles and aunties, all with their jobs to do, somewhere on the spectrum from grief-counselling to hearse-ordering, depending on their skill-set.

All except me. As the little-known girlfriend of one of the grandsons, I felt acutely in the way. Awkward, a noisy presence (although I rarely spoke) during a time when the family needed to close in, bunker down, and support one another.

Often, food is how we show someone we love them, when they are going through a difficult time. Something hearty and lovingly baked, and left at the doorstep to be consumed when there’s no time or energy left for cooking, or frozen for a later day.

But as a superfluous guest in the bereaved person’s house, I couldn’t do that, so I made the next best thing: tea. Pots and pots of tea. I made so much tea, in fact, that everyone got sick of it. I distinctly remember walking into the kitchen where my boyfriend’s mother and grandmother sat together over the table by the window, and offering to put on the kettle. “I think we’ve all had enough cups of tea for today, thank you Naomi,” they said.

We had a bereavement in our family this week and, once gain, my mind turned to food.

I can’t erase the pain of those who are most affected, but I can sit in the stillness with them. (I have learned, since my 20s, that sometimes it is OK to be still with someone. We don’t always have to be doing, doing, doing). And the other thing I can do, this time, is make food. Nutritious food because grief can take a toll on the body. Hearty meals because they feel like edible hugs. Handy dishes that only need to be heated up to feed a whole family. And sweet treats, for emotional self-care and to have something easy to offer the inevitable well-meaning guests who drop around.

It was serendipitous, also, that the day after we lost our loved-one, I received a gift in the mail from Sophie Hansen (of Local is Lovely): her latest cookbook, A Basket by the Door. Actually, I received two copies of this book on the one day, one that I had pre-ordered, and another as a personal gift from Sophie.

Sophie’s book is all about food that is made to be given away. The edible care packages through which we share love during the large and small milestones of life: the loss of a loved one, a new baby, a school picnic, pre-exam jitters, a graduation, welcoming a new neighbour… and the list goes on.

This is such a heartwarming concept for a book, don’t you think? There is nothing fancy or flashy in here, and most of the recipes are relatively easy to make. The goal is to share love, not show off. Delicious, tasty, wholesome food that is intended to be given away (although Sophie does make the clever suggestion that we double some of the recipes, to keep some for ourselves as well!), alongside practical tips on how to ensure it travels well.

Country hospitality.

(I realise at this point that this is starting to sound like a sponsored post: I assure you it’s not. I bought my own copy of this lovely book, and nobody asked me to write about it. I just really, really adore the concept of edible care packages, and even I can cook these recipes!)

For my grieving family, from A Basket by the Door, I have already made a rich and hearty lasagne, half to eat now and half to freeze for another day when cooking feels like too much. I’ve prepared a simple and delicious filling for chicken sandwiches so we can stuff it into crusty bread rolls and take it to the park to recharge in nature. I plan to make and freeze some bliss balls during the school holidays for the kids to take in their lunch boxes when term starts, and there’s a coconut and lemongrass broth that has caught my eye for dinner some night soon.

I baked the blueberry, lemon and rosemary cake you see in the photograph above this afternoon, as a treat for the children when they came home from school, tired, grubby and low on reserves. (It freezes well so there’s a lot of future after-school treats in that tin!)

Sophie made all the food for this book, and photographed it, herself, over two years. Doing it this way - slowly, thoughtfully - meant the food she made was shared in the way it was intended, with family and friends, each dish an individual act of abundance and love.

In this spirit, I was thinking I’d like to send you a care package, too, to say thank you for being my community.

This blog is my happy place. I called it “Naomi Loves” many years ago, because I wanted it to be a celebration of the things, places and people I love, and that has never changed. In fact, of late I have really fallen back in love with this form of storytelling, and it gives me great joy to write a blog post each week.

But what really makes me swoon about this blog is you. In 2019, when so many people are saying blogging is dead and the only real community is on social media, you are here. You read, you leave your comments, you send me emails, and I cannot tell you how wonderful I feel to know that we are sharing this little time together, and that you allow me into your world in this small way.

Those of us here on this blog are a much smaller community than on my Instagram or my newsletter, but that makes it feel all-the-more intimate when I am writing to you, and I feel I can be more vulnerable here than anywhere else in public. It’s almost as though we’re family.

And so, I want to thank you. I’d like to give you my second copy of A Basket by the Door (the one I paid for, because the one Sophie gave me has a little note in it that makes it extra special to me). I won’t post this opportunity anywhere else online, I’m keeping it only for this little blog community, because I appreciate you so much.

If you think you’d like A Basket by the Door, either for you or a friend, simply leave me a comment in this post below (if you’re reading this via email you just need to click on the title of this blog post to see it in your browser, and then you’ll see the comment box), letting me know what your favourite ‘edible care package’ is (either to give or to receive), and what makes it special. (Mine is chicken pie, but the why of that is another story for another day).

I know some of you have missed out on past opportunities on this blog because of time zones, so this time we can take it slow. I’ll choose a winner a week from today, on Friday evening, Australian Eastern Standard Time, and email that person. The opportunity is open to you anywhere in the world and, depending on the laws in your country, I might bake you a batch of my mother’s Anzac biscuits (they travel well) to go with the book.

Big hugs,

Naomi xo

UPDATE 15/04/19: This competition is now closed, and the winner has been notified. But if you’re in the mood for some inspiration, have a browse through all the kitchen-generosity in the comments below. It’s utterly heartwarming! And do still feel free to share your thoughts on this. The community on this blog genuinely makes it my happy place.

The memory-map

The first thing I painted was the 14th-Century chateau, one night after we had explored it with our friend Tonia. We’d set out early that morning with a backpack stuffed with chopped vegetables, bananas, baguettes and the homemade koulourakia we’d baked the day before from a Meals in the Mail recipe, to walk the ramparts all the way around town.

At the chateau we stopped to catch our breath and polish off our little lunch, sitting on the ancient stone wall amid glorious pink and red flowers, before buying four tickets at the gate and heading inside to explore. The chateau is formally known as “donjon de la duchesse Anne,” or “the keep of Duchess Anne,” a woman beloved as a ruler and protector of Brittany from 1488 until her death, as well as being Queen Consort of France (twice).

Today, her keep is almost empty: no roped-off antiques or baltic pine replicas here, just empty rooms with carved shutters half-closed over diamond-paned windows. It made space for the ghosts, and we could almost feel the past walking among us in those empty rooms. We climbed the narrow spiral-stone staircase up, up, wandering the rooms where once the Duchess Anne ate, conversed and slept, until we emerged to blinding sun and gusting winds on the roof. Then we headed down. Down, down, into the smoke-stained ‘dungeon’ of a kitchen, where there were no windows and Tonia and I had to use our iPhones as torches so that we could all make it down the final flight of stairs without breaking any limbs.

At various levels (especially in the guards’ rooms), medieval toilets were cut into the stone and, from the smell, were still occasionally in use. We only just - with seconds to spare - managed to stop four-year-old Ralph from doing the same, and the laughter from our little party at this lucky escape carried us all the way back to our still-new (to us) apartment.

So later that night, when the children were sleeping the deserved sleep of the utterly exhausted and Tonia and I sat up eating cheese and drinking rosé, I drew the chateau on the blank paper of my future map, and wrote our little story down next to it.

Piece by piece, as we built memories, I added them to the map. Picnics at the nearby ruins. Baguettes from our favourite boulangerie. Trips to Saint Malo, le Mont Saint Michel, and Broceliande. The carousel the children loved to ride, where first Scout announced, “Our town is amazing!” The church with the bells that punctuated our days and nights with such beauty. The big, old English sheepdog we called Sarah, from that time I said “Look, that dog has it’s hair up” and Ralph replied, “How do you know it’s called Sarah?”

Painting at night after each adventure, there wasn’t any strategy or forethought to the map, and this made for lots of mistakes. I painted the Thursday markets one evening after carrying home the week’s bounty, and, a few days later, drew in the clock tower behind it after we had climbed to the top. Then a month or two further along, when I decided I needed to paint in the grand old buildings that lined the market square, the clock tower was already in the way. In my painting it has grown legs and journeyed a full block away from the rue de l’horloge, where it stood since 1498. I drew Sarah the dog before adding in the buildings around her, and it turned out she was not even remotely to scale. I had accidentally turned her into a canine giant, eclipsed only by the baguettes, which are the size of some houses. Saint Malo was on a wonky slope, the abbey at Lehon slid over onto the very bottom of the paper, and a strange, ibex-like creature on the carousel loomed over everything else.

The mistakes have come to be my favourite parts of this map. I could have waited, of course, collecting these moments in my mind to faithfully reproduce them back home. Carefully copying or tracing a roadmap of Dinan, and then plotting out our favourite memories with both accuracy and artistic arrangement.

In fact, that was my original intention in making the map. After taking multiple wrong turns when trying to follow the map of the ramparts given to us by the Dinan tourism office, Tonia and I joked that I’d paint a more accurate one, and give it to them when we left.

But the best adventures are unplanned and precious moments come unbidden. And if you don’t stop to notice them when they happen, those moments can journey on by, altogether unseen.

So I chose mindfulness over method, thankfulness over design, and pasted my little acts of gratitude like patchwork all over the paper, living each drawing in the moment without pausing to plan the final piece.

When we left the village in December, I didn’t know what to do with the map. The handmade paper was so thick and large it couldn’t fit into a tube, so I carried it with me from Dinan to Paris, Paris to London, London to Cumbria, Cumbria to Inverness, Inverness to Edinburgh, and Edinburgh to Melbourne, Australia. After we returned home, it lay rolled up and forgotten on the sofa-bed in our front room for a month, buried under clothes awaiting dry-cleaning, until finally in mid-February I uncovered it and found the time - and emotional fortitude - to finish what I had started on that hot summer’s day at the chateau, back in August.

So here it is, in all its wonky, unplanned, mistake-ridden, navigationally-bereft, emotionally-rich glory. The story-map of our sabbatical in France, and a pen-and-paint act of thanksgiving.

Ode to doing nothing

In the beginning, the silence is uncanny. You can’t hear anything at all, not at first. But you have to let yourself go completely still.

Then you realise there are birds in the distant trees. Nearby, a cicada calls. Then the wind picks up and trees begin whispering to one another, and now you can hear the creaks and cracks that are the growing pains of the ancient bush. Hidden rustlings of secret creatures, the crunch of bark underfoot, the hum of something winged buzzing just past your ear.

And you realise the silence is actually a cacophony, and that the empty landscape is a crowd.

We have been staying on a friend’s farm, in the Macedon mountain ranges about an hour outside Melbourne.

The fields at the moment are, appropriately, autumnal gold. They might be the freshly-shorn fields of an autumn harvest, but then again they might just be the visible remnants of a brutally hot summer. Either way they are, undisputedly, gold. And more beautiful than you could imagine.

Smooth gusts of wind make patterns in the grass in gold and sand, as though unseen gods are passing by and gently stroking their hands over the grass. As perhaps they are.

In the afternoon I take a walk through the trees and then sit down amid the grass to listen to the wind. One of the horses in the bottom paddock spots me and nickers hopefully, wanting carrots. I’m empty handed, but I walk across to him and stroke his soft nose, then bend and breathe into his nostrils, the way I was taught to do with horses when I was a child.

His earthy, honey-breath is achingly familiar, and I feel a stab of love for my own beautiful old horse, Starbrow. Did you know that horse-breath smells like honey? I used to sit in the grass in our own paddock as a teenager, and Starbrow would wander over to pass the time. I’d breathe in his honey-breath, and stroke his nose until his eyelids drooped and he fell asleep on his feet, with his head in my lap.

Those were days in my life when sitting still meant actually doing nothing. I wasn’t multitasking, I didn’t carry a phone, and I didn’t even own a laptop. The only ‘data’ I was consuming was the touch of the wind on my bare arms, the sound of lorikeets bickering in the trees behind us, the sandpaper prickle of the bracken where I sat, and the scent of this sleepy old horse with his head resting on my crossed legs.

On the weekend, we sat still again.

We sat in the shade of a tree beside the dam, while the children fed about twenty ducks that felt like a hundred ducks, three pushy ‘bin-birds,’ and one very courageous magpie. When the children were all out of food, the ducks retreated to the shade of a willow-tree on a little island, and Scout and Ralph retreated to our spot on the banks of the dam, where we all proceeded to do… nothing much.

Scout leaned against us and methodically worked away on the friendship bracelet she’d been taught to weave by the little girl at the Girl Guides stall at the markets that morning. Ralph emptied the bag of cars he’d purchased for $1 at the same market onto the ground, and began digging a dirt track in which to race them.

And Mr B and I talked. We talked like we so rarely get to talk these days, about nothing, which felt like everything. We told each other stories, shared jokes, made plans, and dreamed dreams. And as the afternoon slowly unfolded it felt as though we were rediscovering each other. Mr B and I are always good friends, but the roles we play throughout the day (our “jobs,” if you want to think about this in career terms) are so different from one another that we can easily go through life feeling more apart than we actually are. But that afternoon under the tree doing nothing was a reminder of how much we shared, in opinions and in ethics and in life, despite our separate daily experiences.

It was a lovely gift, and something we could only have experienced because we gave ourselves permission to do nothing. In that afternoon, I felt a rush of affection for the man I married.

Right now I’m working on an article for a magazine, and it’s about the way that building “white space” into our days can free up our creative ideas and inspiration. Or, to put it in terms I heard at the My Open Kitchen gathering last year, “While ever you are consuming, you are not creating.”

It’s a subject I teach on and a subject I’ve been researching for this article. But sometimes we have to live something, don’t we, before the lesson can move from head to heart. Finally - finally - on the weekend, I stopped. At least for a little while. And I learned my own lesson.

White space - boredom - unplugging - stopping - doing nothing… no matter what you want to call it, it’s the stopping that can kick-start the new beginnings. In creativity, in ideas, in love, and in life.

Wouldn’t you agree?

Golden

Those were golden days.

When we arrived in Dinan, our park was a rainbow cacophony of flowers in bloom, but in the weeks that followed we watched the flowers fade, and the chestnuts begin to drop. The path we walked to get to the playground (the path you see in the picture above above) was like being inside the colour green. The air itself felt green, and the still-warm afternoons were soft, like a hug from nature.

But then, while our backs were turned, everything changed.

The temperatures dropped, and we returned to the playground after a week doing other things to discover green had receded, in the most magnificent of fashions. The park was now shocking, and glorious, and unabashedly golden.

I like to think there is a metaphor in this park for the gold-tinted nostalgia I know I will feel for our sojourn in France in the months and years to come.

There are some things I won’t miss, of course. Being apart from the children’s father for so long tops that list, but I also won’t miss dodging dog-poo on the footpaths, the oven that burned everything, the ever-present smell of cigarette-smoke in the hallway that filtered through to the bathroom and bedrooms, and the incredibly uncomfortable mattresses. The unreliable buses, the way our apartment never felt properly clean… and it will be a long time before I ever want to eat another galette blé noir.

But this park, these children, those are the gold-tinted memories I will carry with me in the years to come. Memories that will turn into nostalgia, long after I have forgotten the grumpy British man downstairs, who liked to complain about the thumps my children made on the floor when they got up in the morning. (It must have been annoying, but there wasn’t much I could do: they haven’t yet learned how to levitate).

Nine hundred kilometres. That’s how far (actually it was a bit further) my children walked during our three months in France. These are the same little legs that were apparently “too tired” to walk the 15 minutes it took to take Scout to school every day last year. Or the three-block stroll to the park.

In France, they would walk, and walk, and walk. And when we stopped walking, they would run, and leap, and dance. I know how far they walked because of the little ‘steps’ app on my ‘phone, by which I kept a tally because the children were so proud of themselves, discovering stamina and resilience they didn’t know they had.

Pepper. That’s how Ralph likes to season his food now. Scout likes her mayonnaise homemade, with enough mustard to give it tang. They eat ‘real’ sushi, tuna salads, vegetable soups, seared steak and soft cheese. They crack their own walnuts and eat them out of the shell. They devour giant bowls of moules marinières (avec frites), homemade muesli, and milk-jelly made using a recipe from Henry VIII’s kitchen. In short, they developed palates in France. And better still, they gained a sense of culinary adventure. Gone are the days of plain pasta and never-ending towers of ham-and-cheese toasties, and chicken nuggets at cafes. Now, they eat what we eat.

When Scout left for Australia she was afraid of all animals. By the time she returned, she was able to play with dogs, ride horses, and care for our baby bunny. At some point in November, while tucked up in bed in our chilly apartment in Dinan, Scout also discovered she could tell stories, and began spinning fabulous and fantastical yarns about faraway adventures, when previously she’d only understood narrative recall.

Ralph began using French words instead of English ones in conversation, without realising he was doing it (and still insisting he couldn’t understand French). He also found the language he needed to describe his emotions, which sometimes threatened to overwhelm him (and then us) when he was tired. He invented phrases like “letting the wolf out” to describe that feeling when anger and frustration took over, so he could tell us what was happening on the inside, before the situation escalated on the outside.

Ralph grappled languages and feelings and currencies and public transport and dropped day-naps with the kind of resilience none of us could have imagined before we left Australia.

But perhaps the most beautiful change I saw - even more beautiful than the foliage change from summer to autumn in our playground - was in their relationship. The children have always been close, a happy side-effect of being born so close together (only 17 months apart), and of sharing a bedroom.

But I watched their friendship blossom in France, alongside their shared experiences and, despite the inevitable arguments, they became a true unit. It wasn’t just friendship: it was trust, reliance, comfort, compassion, and support. The word that comes to me is “tribe.” They became one another’s tribe, and gave one another a sense of belonging that kept them feeling secure despite all the changes and new experiences. It’s something I hope and pray will stay with them throughout their lives.

Because it is golden.

Harvest and home

Autumn swept into Melbourne last week with one last, brutal heatwave, scorching gardens and people alike, and reminding us that our place on this brown and sunburned land is insubstantial. In my family, the threads that tie us to this landscape are gossamer, only two generations young, and our biology has not caught up with our climate. Every time the mercury rises we are driven inside, hiding from the weather in the relative cool of double-brick walls and high ceilings and air conditioning.

Autumn is harvest time, usually a season of delicious bounty, but heatwaves here and drought there and floods over there have left many of my country’s crops rotting, or burned away, or not even planted. Often we are insulated from these events in the city, the travails of the farmers and producers only an hour or two away from us go unnoticed amid bulk discount produce in the supermarket, shipped in on ice from many thousands of kilometres away. But when a head of broccoli soars to $10.75 a kilo, surely more people will start to take notice.

We do our best to buy locally, supporting our farmers or the high-street shops that in turn support the farmers, and we follow the seasons as best we can, buying our food when it is at its best and was picked just the other day and just around the corner (rather than last month and in another time zone).

But if you can’t grow the crops yourself, it’s not always easy to know what is at its best, when.

This was easier in France. Shopping at the farmers’ markets in Dinan every week, I tried to let the produce inspire my cooking, rather than carrying a shopping list with me (I wrote about that in my newsletter last month, and you can read it here if you’d like to).

I quickly learned from this experience how ill-equipped I was as a cook to plan our meals in this way, and scouted around for some kind of guide to help me. And, this being France, naturally I found one. It was a little book called “Agenda Gourmand: use année de recites avec des produits de saison” (which is fairly self-explanatory even if you don’t speak French, but roughly means “Food planner: yearly recipes with seasonal produce”). There was a week to each opening, celebrating the produce that was likely to be at its best on that particular week, and sharing recipes and other tips for using and cooking with them.

Back in Melbourne now, I have decided to create - and paint - an agenda gourmand of my own, noting down the best times to plant, harvest, buy and forage for food where I live, and collecting my favourite recipes, remedies and stories for making use of them. I hope it will become my go-to food guide for seasonal eating, and maybe something I can pass down to my children as well.

I also hope it will become a celebration of the beauty and abundance of nature, both in paint and in words. Another way for me to make peace with my country, even when the heatwaves are relentless and fierce.

So I have started painting, and I have started reminiscing…

Pears…

They were never my favourite. Too sweet, too juicy, and with that funny, fuzzy texture on the tongue… not for me. (Although hard to surpass in a rocket salad with parmesan cheese and rocket, it’s true, to complement the pork ragu I like to make in autumn).

And then there was that tarte au poire I ate atop the Eiffel Tower in the autumn of 2011, on the holiday from which, unknowing at the time, I would bring my daughter home inside me.

September was cooling down. It had been raining, and parts of the metal steps were slippery as I climbed, alongside two friends I’d known and loved since childhood. I’d been to Paris before but this was my first time climbing the tower, and no amount of cliché, nor the blisters from the new red ballet-flats I’d mistakenly thought would be romantic on a visit to Paris, could make the moment less magical.

At the top we bought hot chocolates, and my friend Lindy chose a pear tart for us to share. It was one of those moments. Paris in the rain. The Eiffel Tower. Beloved friends… and that tart. Sweet, vanilla pastry, a hint of almonds, and juicy pears (fresh, with the skin still on them) arranged in a beautiful flower and glowing under a delicate glaze.

That was the day I made friends with pears.

Radishes…

Sharp and clean, with a pepper-like crunch that warms a winter salad and makes orange sing. Slice them thinly, then hold the slices up to a window to see them glow like tiny moons.

Radishes are the first vegetable I remember growing. My mother found us a little patch of dirt around the side of our suburban house in Berowra Heights, and told us we could grow our very own vegetables. She told me she chose radishes because they were so easy to grow, even in cooler weather, and they were relatively quick: you have to harvest radishes early or they become hot and spongy.

I remember the touch of the warm soil as I drew a line in my little vegetable patch with my finger, carving a trench just deep enough to carefully place the seeds along the line I’d made, each of them two hands apart, before covering and gently patting the soil smooth again. The staggering weight of the watering can as I tilted it over my future harvest, barely able to hold it up. And the excitement when the first, green shoots poked up through that carefully tended soil… And then the waiting - oh! the waiting! - with the sublime impatience of childhood, for the harvest day to come.

Something else I remember: the extraordinary underwhelm of my first bite. Pepper! I suspect I wailed, “Too hot!” The flavour that now brings me so much delight (is there anything better, paired with pomegranate seeds, watercress, honey and fresh mint?) was a resounding failure in my childhood vegetable patch. I don’t remember what came next. Carrots, maybe?

Apples…

The apple tree at the front of our house is fruiting this year. It’s just a crabapple tree, nothing we can pick and munch for morning tea like the gala apple I’ve painted here (I had to label it in the ‘fridge: “Mummy’s art, don’t eat.”) I chose the crabapple for our tiny front yard because the blossom trees on the next street over were so spectacular that in spring they would take your breath away. I think you could see those rows of blossoms from space, and that’s something special in the inner city. I love these trees so much I contacted the chief arborist at our local council to find out exactly what variety they were, so I could have my very own piece of blossom heaven.

I missed the blooms on our tree last year, because we were in France, but my husband tells me they were every bit as glorious as I’d hoped. And now our little tree is fruiting. Every morning as the children and I set off on our walk to school, we say hello to our tree and inspect the baby fruit, which seems simultaneously so improbable and yet so lovely in our tiny city yard.

In Dinan, there was a public apple orchard. Mostly cider apples, growing wild and unharvested on the side of the hill beneath the castle walls. There was a path winding through the apple-trees down to the river (they called the path a ‘Chemin des Pommiers’ - an apple walk), so covered in fallen apples in October that a gentle stroll became a slippery and treacherous clamber. But the air inside the orchard was perfumed with apple-flavoured honey.

Also this podcast about apple trees, with Lindsay Cameron Wilson, makes me so happy.

What are your stories?

Midwinter mystery

I wanted to watch the sun rise through the standing stones on the winter solstice.

In truth, the true magic was supposed to happen at sunset: the last of the day’s light beaming through the passageways of the southwest-facing cairns and spilling over the ancient dead like a gift, for a few precious moments in this one important hour every year, for four thousand years.

But sunset in mid December was at 3.30 in the afternoon, and I knew we’d probably still be out. We had made plans to visit a tiny village close to Nairn, and walk ten kilometres though fields to see Cawdor Castle in the distance, the seat of my distant Calder relatives. Probably, I thought, we’d still be driving home at sunset. (We were).

And the forecast was for rain in the afternoon, anyway.

So we hurried down our breakfast and left in the dark, arriving just in time to watch the dawn instead, as it coloured the ancient wood in gold, and sent the fairies shimmering back into the shadows, seconds before the sun’s rays broke then burst over the nearby hills.

My family wandered with me for a few minutes but then retreated to the relative warmth of the car, leaving me to explore the cairns and stones alone.

For a little while, I pulled my gloves off and rested my fingertips on the ancient standing stones, letting the earth’s currents flow up through that quiet ground and the lichen-covered stone, then coursing into my hands and grounding my body in nature and history.

Four thousand years. It’s an almost unthinkable age to me but, to our planet, those stones are little more than the passing acne of adolescence on the surface of time.

The stones were sharp with ice, and smooth inside the “cups,” little circular dips carved out with stone or antler tools, patiently worked by human hands millennia ago. Hands just like mine, maybe even genetically related to mine, but on people leading lives so different to my experience it is impossible to fathom that which binds us.

Except this earth. This dawn. These stones. They are our constant, linking me to them and them to me as though time did not matter and they had just - just - left, melting away into shadows with the fairies mere moments before I arrived with the sun.

Who were they?

These ancient ancestors of ours positioned the cairns to catch the solstice sunset, and graded the standing stones around them according to astronomical axes. Those that face the sunrise are smaller and whiter, while those placed toward the sunset are larger and the lichen, when scraped away, reveals stones of pink and red.

Artists of the earth.

While I stood alone and watched, the morning sun pierced a cleft stone in the lonely field.

On a whim, I stepped behind the stone and let the cut-light pierce and refract over my face, closing my eyes to the gold, and turning it red beneath my lids.

What do you think it means, that split stone? It is not the biggest nor the most impressive of the standing stones that guard these cairns, but the cleft feels strange, not something you see in nature, and to me it feels like a question. Two almost identical pieces of stone, side by side, kissing at the base but pushing one another apart at the shoulders, creating unearthly shadows and bending the sun’s rays and creating a hard-to-pin-down sense of unease.

Like listening to your parents argue in the next room.

Our humanity unites us throughout the millennia. These stones are part of me and I am part of them. But what do they mean?

Lessons from the summer garden

I have been waiting for the weather to cool.

The summer’s evening we returned home from France, I stood in my little garden in the shocking humidity, and took these pictures. It was a jungle. Abundant and overgrown, some plants thriving and other plants choking, and I made plans to gently nurture it back to life. My very own Secret Garden.

I made a start, cutting back the valerian and unwinding the clematis so the other plants could breathe. There was no saving the blueberry bush, one of the hydrangeas or two of the camellias. Two out of three of the Japanese maples were looking decidedly sad.

But I still held out hope for the roses, the pomegranate, and my favourite oak-leaf hydrangea, and the honeysuckle was so healthy it had all-but swallowed the children’s cubby house whole.

But instead of making it better, I only made things worse. Clearing away the overgrown vines left my space-starved plants vulnerable when the heat came - and come it did, less than a week later, in waves of day after day with temperatures in the late 30s and early 40s, Celsius.

No amount of water can keep alive a plant that is being literally burned from the sky. One of my happily-blooming fuchsias was the first to go. At the end of one particularly long, hot day (long after dark it was still 36 degrees), every leaf had turned brown. When I cupped the leaves in my hand, they fell from the stems and crumbled to dust.

The little Jack Frost plants soon followed suit, and most of the Japanese windflowers. Soon my gardenias were looking sad, the oak-leaf hydrangea crisped at all the edges, and the leaves began dropping off the Japanese maple.

None of the border plants survived, and brown began to swallow green.

The poets of ancient Jerusalem wrote, “To everything there is a season.” (Or were they quoting Pete Seeger?) And nowhere is that more evident than in an actual garden, where the seasons govern, and human intervention can only go so far in changing or mitigating what nature intends.

One of the things I noticed about the public flower gardens in France was that in spring and summer, they were more beautiful than anything you could imagine: full of shocking, extravagant colour like a fragrant, bee-filled rainbow explosion. But when autumn came and the seed-heads drooped, gardeners cut everything back, aerated the ground, and let it rest for the cooler months. It wasn’t pretty: brown patches of earth with the odd leftover strand of sad annual eking out the last of its days.

We don’t tend to do that in Australia. We plant and tend for year-round cover, and seek colour in every season. I know I’ve tried this in my own little garden, filling those brown patches as best I can in winter so we only look out on green.

But respecting the season means working with nature, rather than fighting it.

Those plants in my garden shouldn’t have been left to smother one another but, once it was done, I should have known better than to strip things bare right when the worst of the heat was about to begin. And I had known it would begin: January and February where I live are the hottest months of the year.

But I was impatient, eager to reconnect with my home by putting my hands in the earth, and I wouldn’t wait. In many parts of Europe, brown and grey are the colours of winter. I made them the colour of Melbourne in summer, too.

Gardens teach us patience, if we will let them. To everything there is a season. There is a season for brown, and a season for colour. A season for hot, and a season for cold.

A season for abundance, and a season for rest.

My friend Brenner and I send one another voice-messages most days, little audio missives that carry with them the ambience of our respective worlds. In mine, while soaring temperatures burn everything around me and sting my eyelashes, there is a heartbreaking crunch of dry things underfoot as I walk and talk. In Brenner’s messages, sent to me from her home in tropical far-north Queensland, I hear frogs and cicadas, and the soft and ever-present sound of rain. Up there, these seasons aren’t spring-summer-autumn-winter. They are known as the wet season, and the dry.

Nature comes back.

Even my burnt plants will re-shoot leaves. And if they don’t, others will clamber over and take their place.

So I will wait. When the weather cools, I will replant but, when winter comes, I will allow my garden to rest. To lie fallow, the way nature intended. It’s ok, I will remind it, to be brown.

Come spring, I hope I can bring you a rainbow.

Ten days of illustrations

I’m just past 10 days into the #100DaysinDinan project, and so far I am loving it! As I had hoped, taking out the time to draw these pictures each day is taking me back to our time in the village, and how it has influenced me and my family in big ways and small.

To jog my memory and find things to paint, I’ve been scrolling through photos in my camera, and that has been an extra-welcome trip down memory lane. The children love to see what I’ve been painting each day, often chiming in with “Remember when…?” as they hold the little cards in their hands.

I’m making the envelopes for each card by tracing one of the original envelopes the cards came in, onto used calendars and magazine pages. A stamp or two, and the address: there’s not much room for anything else, so into the post they go.

Here are the first 10 that I’ve painted and posted, with a bit of the back-story behind them.

hotel de beaumanoir

The beautiful, 15th-century archway to the former hotel de Beaumanoir: 1 rue Haute-Voie, Dinan. This was just around the corner from our apartment and after dropping off our bags on Day 1, we took a wander through town. This intricate stone archway took my breath away, and I couldn’t believe I was going to live in such a place

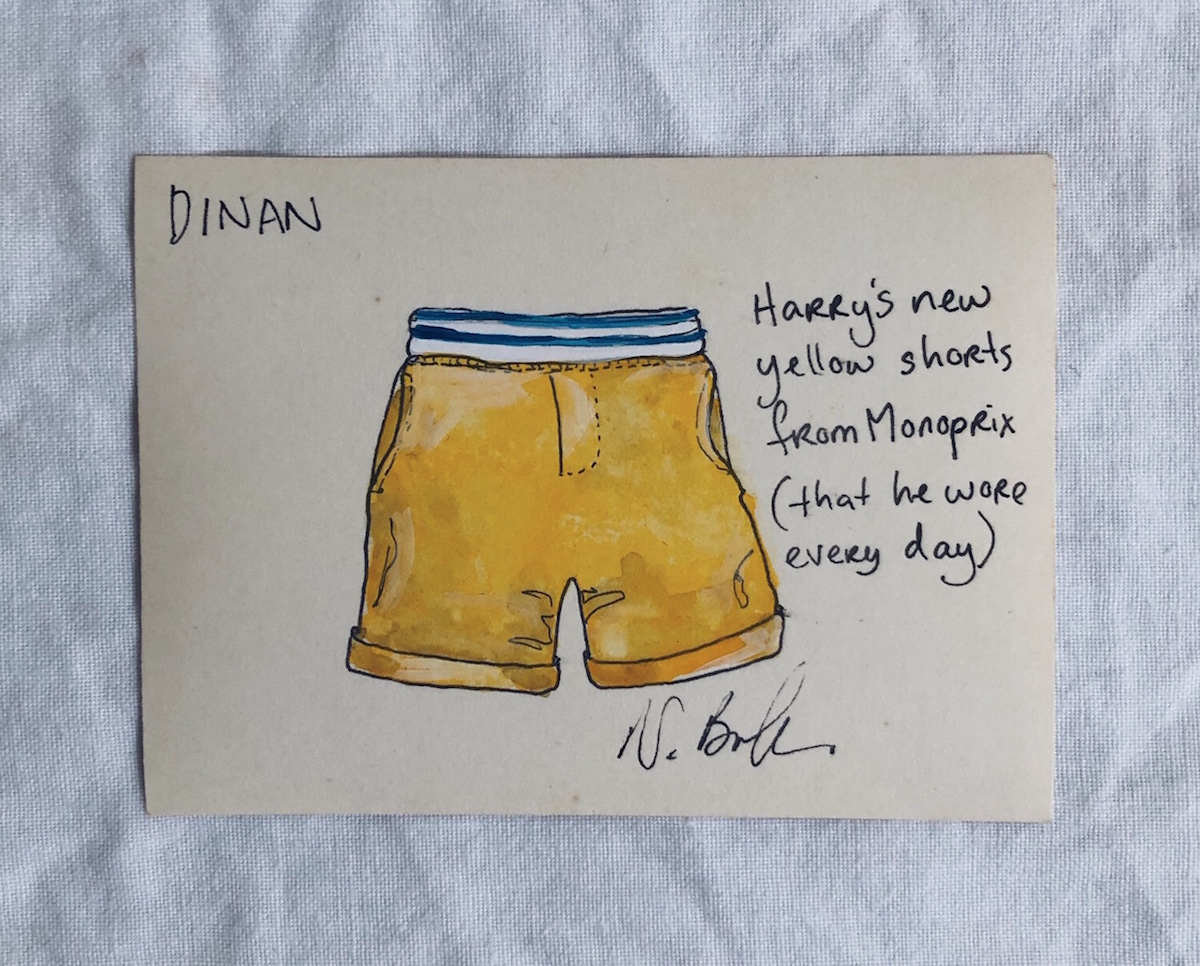

new yellow shorts

We arrived in France from the coldest month of winter in Australia, with very few summer clothes in the suitcase as the children had already grown out of theirs from six months earlier. While riding the carousel in the hot sun the day after our arrival, four-year-old Ralph found his jeans just - too - hot. I popped into the Monoprix and bought him these sweet yellow shorts, which he loved so much that he wore them nearly every day until the end of summer

maison bazille

There are several chocolatiers in Dinan, and we sampled them all! Our favourite was Maison Bazille on 10 Rue de l'Apport. Partly for the silky homemade chocolate (made on the premises) with all kinds of flavoured ganache, and partly for the macarons, but mostly because Anne, the proprietress, was just so lovely. She would welcome us with beaming smiles, and when we returned after three weeks in the UK, she gave the children cuddles and kisses. We would slow down every time we walked past, in order to catch her eye and wave

half-timbered houses

Dinan is famous in France for the half-timbered houses that line its streets. They are crooked and wonky, because when they were built (mostly the 14th and 15th Centuries) there was a tax on floor-space at the ground floor, so people built small at the base and increasingly spread out as they built up. (This particular house is now a restaurant, La Mere Pourcel on 3 Place des Merciers. I really wanted to eat there but it looked too fancy for a mum and two kids, so I’ll have to go next time!)

moules-frites marinieres

Ralph was gung-ho with the moules-frites from the very beginning, but Scout only discovered them during a visit to Mont Saint-Michel. It was a steaming hot day, and we sheltered from the sun in a restaurant for lunch. I’d ordered myself a bowl of moules-frites while the children had pizza, but Scout ended up stealing more than three-quarters of my mussels. We told the proprietress they were the best we’d ever tasted, and she smiled and shrugged, “c’est la saison” (it’s the season)

rampart towers

There are lovely little towers in the castle walls all the way around Dinan. This one is over one of the steep streets that lead between the hilltop part of the town, and the ancient river port. The children and I would walk along the ramparts on the way home from school, and stop to take in the view from the top of this tower

the padlock letterbox

The steep, cobblestoned rue du petit fort leads all the way down to the river at Dinan, and the whole way down the little street is lined with ancient and fascinating homes, shops and cafes. This door is almost at the bottom, and boasts the biggest padlock you have ever seen, which now does duty as a private letterbox

sea-birds

Dinan doesn’t feel like a seaside town. There is a river, to be sure, but it no longer dominates the landscape or trade, ever since the town moved up the hill and behind the castle walls for safety, many hundreds of years ago. But this is the west coast of Brittany, and the sea is still close enough that sea-birds call and circle in the morning, and wander through the streets hoping for scraps from tourists at lunch

boats on the canal

The river Rance, by the time it gets to Dinan, is little more than a canal. The first week we arrived, we took a ride on a river-boat up the canal to the neighbouring town of Lehon, the children fascinated when we had to stop at a lock and wait for the water to rise. There was a path beside the canal where horses used to walk and pull the boats. Once, a family’s horse sadly died, so the captain’s wife had to ‘harness up’ and pull the boat herself. There are photos. In the summer, weekender boats like this one I’ve painted would chug past and we’d wave at them

birkenstock kilometres

The day before we left on our adventure, we took the children to the Birkenstock store in Melbourne and picked up a pair of sandals each. It was winter here in Australia, and they had long grown-out of their sandals from the previous summer. When we arrived in France, those sandals became synonymous with the new sense of adventure and resilience my children developed. From complaining about a two-block walk in Australia, they cheerfully walked 10+ kilometres every day in those sandals

The wuthering north

We drove into Cumbria after dark, just as the winds were picking up. Outside it was right on zero degrees, although the little weather app on my iPhone said, helpfully, “feels like -6”. It did.

The journey had been almost twice as long as we’d anticipated, an unlucky accumulation of London traffic that had continued for three hours outside London; a sun that set at half-past-three in the afternoon, leaving us to navigate our oversized hire-car through steep and winding country roads after dark; and, speaking of navigation, numerous opportunities to take wrong turns and get lost, which we did (there were even road-signs saying “don’t trust the sat-nav”).

From bed that night I could just see the soft, watery light of the crescent moon behind the still-gathering clouds, filtering and refracting through diamond-paned windows that had filtered and refracted moonlight into this room for 500 years, exaggerating the shadows of the beams in our ceiling. The wind was picking up, battering around the ancient walls of our gatehouse in a beautiful fury.

“I love it here,” I whispered to my husband, although he might already have been asleep. “I can’t even tell you. I really love it here!”

The moon was long gone by morning, and the sun was doing its best job of hiding, too, but the grey dawn revealed bare trees and stone walls and crumbling ruins and bracken-covered hills as far as the eye could see. I ran outside in my slippers, hugging my pyjamas close, and drew in the wild view like oxygen.

Back inside, I put on the kettle and made eggs on toast for my family, while the wind positively howled. “Wow!” said the children (about the weather, not my eggs). And as we sat down at the farmhouse table under a window, beside a cast-iron fire that was cracking and popping and spreading warmth, I thought, “We are inside Wuthering Heights.”

Naturally, there was a pretty village nearby, where one could find welcoming locals with musical accents and a cafe with cockle-warming, home-cooked meals. Also naturally, there was a castle ruin, a 900-year-old edifice on an ancient mound that was once settled by Danes and was still part of Scotland until a thousand years ago or so.

I climbed the hill to the ruins alone, while the rest of my family went to find somewhere to buy groceries. The promised “ice rain” had begun, and I have honestly never felt as cold as I did atop that wild and windswept hill, not even on the January night I walked home beside the Hudson River in New York with my friend, and we learned later that it had been -18 degrees.

It was the wind. The wind that burned my ears with cold like razors, stung my eyes with dry tears, tipped me sideways, and genuinely sucked the breath from my lungs whenever I faced into it. Literally breathtaking.

How is it that this world is so full of so many beautiful places? How can we bear it, in our hearts? We only stayed in this ancient gatehouse, perched on the edge of lovely emptiness, for two nights, but I cried for the beauty of it all three times.

I didn’t want to leave. But then, that’s also how I’d felt when first we climbed the steep, cobblestoned streets of Dinan, when we made our picnic under the trees at the castle ruins of Lehon, when we lay down in sunshine among fields of wildflowers in the grounds of Hever Castle, and when we lost ourselves inside the ancient, golden-hued forest of Broceliande. I know I’ve talked about this on my blog before, the twin concepts of home and belonging.

When I married my husband, we made the song Home is wherever I’m with you by Edward Sharpe and the Magnetic Zeroes the unofficial theme-song of our marriage, a testament to where we’d been and where we were going, after I’d left New York to live with him. Every time we moved to a new city, I sought out ways to make it feel like home. I enrolled in a Master’s Degree when we moved to Queensland. I planted a garden when we moved to Sydney. I volunteered when we moved to Adelaide. When we moved to Melbourne, I was already pregnant with my daughter, so new mothers became my community.

I don’t quite know when I started growing restless again. Partly, I think it had to do with having children. The day you hold that new baby in your arms, your world instantly unfolds like a meadow of night-blooming cereus: dazzling flowers, hypnotically-scented, and all opening en masse in one, magic night. But parenthood can also draw your world inside (like the night-blooming cereus closing at dawn, maybe?), and even if you don’t have kids, you’ve heard enough stories from friends and siblings and aunties and grandparents… or read enough mummy-blogs… that you don’t need me to talk about that odd and disorienting and beautiful and isolating parenthood bubble right now.

My point is that becoming a mother, while undeniably the best decision I ever made and the best thing I will ever do, also taught me to see my home-town in a different way. The exciting cafes and galleries and festivals and street-art and food trucks and pop-up events that once helped me fall in love with my city became, almost overnight, all-but lost to me, sitting at home with sleeping (or not-sleeping) babies while my husband worked 100 hours a week.

I have watched the world go on without me, from the distance of the Internet.

And when you take away all the wonderful things about life in the city, you start to notice the restrictive things. The lack of fresh air, open spaces, and trees. The reliance on other things (shops, cars, telephones) for even the most basic necessities of life. With a fidgeting toddler in one arm and a hungry baby in the other, the world feels as though it doesn’t belong to you any more, and for those of us used to being “in control” in the workplace, this new workplace feels about as out of control as workplaces come.

So, as I stood alone on that ancient hilltop in the breath-stealing wind, these were some of the thoughts that were going through my mind. I wanted to live in this place more than I’d wanted to live anywhere, ever. I sort-of cried, again, but I didn’t truly cry, because the wind stung my eyes and dried my tears before they could fall.

We won’t be moving to Cumbria any time soon, no matter how badly I want it. And the truth is that even more than I want that open-fielded life, I want to stay with the people who fill my life right now. They are my home, wherever I go (Home is wherever I’m with you).

After I climbed down from the castle ruins, I found my family in a little second-hand shop on the high street, deep in conversation with three locals who had each lived in this village and known one another for eight decades, or more. They recommended the fish and chips shop for lunch and, an hour or so later when we bustled in from the rain and found somewhere to sit, our new friends were already ensconced around a table at the back.

As we left, my husband secretly paid for their lunch and another round of their coffees, and it’s times like this that I remember why I first made him my home.