JOURNAL

documenting

&

discovering joyful things

Meadow-flowers and sneaky seed-bombs

The week before we left France, I caught up with our friend Rachel, who had been helping the children and I learn French. The children were at Ecole Maternelle that day so it was just me and Rachel. The air was December-cold despite the patchy sun so we sat indoors, at a table by the window, and ordered our coffees.

It was our goodbye: the children’s dad was arriving in a matter of days and then we would all cross the channel for our Christmas holiday in England and Scotland but today, in my final French lesson, Rachel and I wanted to talk about things closer to home. Like the bread vending machine that had been set up in a neighbouring town, because there are laws in France around bread always being available, and the local boulanger had closed down. So the council had a vending machine installed and the bakers from the town next door would stock it every morning with freshly baked baguettes and croissants. Ah, France.

And guerrilla gardening, we talked about guerrilla gardening. Rachel was part of a gardening group in her town that took on the responsibility for beautifying the public areas with green and growing things and, before we said goodbye, she handed me a little packet of seeds. It was a mix of wildflowers that could take root and grow in the tiniest of spaces, the little cracks and grooves between paving, and along the sides of walls. Rachel’s group had been handing these seed packets out for free to residents in their little town, encouraging everyone to scatter them as they walked to encourage diversity and discourage weeds, so now she did the same to me.

I carried the seed-packet home with me and I have been imagining myself as some kind of “meadow-flower Johnny Appleseed” ever since, skipping through Melbourne scattering wildflower-seeds wherever I go, turning my inner-city suburb into a bejewelled field of flowers.

But there are strict biosecurity rules in Australia and so I have never had the courage to open that little packet of seeds. It sits in the 18th Century writing desk I also brought home from France, among other mementoes I hold precious from that time, and has instead inspired home-grown wildflower melanges.

The company behind the seed packet Rachel gave me has been specialising in growing and harvesting meadow flowers for more than 70 years, and they sell mixtures of seeds for every imaginable use. Wildflowers that can be mown over; wildflowers that attract bees; wildflowers that change throughout the seasons. Wildflowers that grow in poor soil; wildflowers for cemeteries; wildflowers for damp and boggy earth. Tall wildflowers, small wildflowers, wildflowers in colours that suggest a medieval carpet (I’m not kidding), and on it goes. Hello, magical occupation envy!

So I have decided to create some wildflower mixes of my own, using seeds safely grown here in Australia. Lacking any handy meadow-space anywhere nearby to create glorious fields of flowers en masse, I’ve gone with “seed bombs” instead, and that’s what I really wanted to share with you in this blog post.

Seed bombs, or seed balls, are simply little balls of clay, compost and seeds, rolled up and left to harden and dry. They are a guerrilla gardener’s best friend because you can just drop these little balls wherever you want your seeds to grow: they’ll sit there innocently until the next proper, soaking rain falls, allowing them to germinate and take root, helped by the tiny starter-soil you’ve given them with the clay and compost.

If you’d like to try making seed bombs, my method is below, along with the “wildflower seed recipe” I created (for medium-height wildflowers that grow well together in spring and summer in a meadow setting, many of them chosen to enrich the soil and encourage pollinators).

If you’ve ever made and shared seed bombs before - or if you give it a try after reading this blog post - I’d love to know how you get on!

Wildflower seed bombs

Wildflower meadow mix

Assorted poppies

Cornflowers

Silene pink

False Queen Anne’s Lace

Chocolate Queen Anne’s Lace

Love-in-a-mist

Flax

Coriander

Alfalfa

Buckwheat

Seed bomb recipe

Equal parts of clay (I used modelling clay from the local art supplies store), and

Compost (I used “zoo poo”)

A handful of vermiculite, a natural mineral that fosters plant growth

Your mix of wildflower seeds (or see mine, left)

Method

In a bucket, soak the clay in some water to soften it and make a mushy, easy-to-manipulate, muddy gloop

Add in the compost and vermiculite and mix them all around with your hands until everything blends together

Sprinkle the seeds over the top, and stir them in with your hands

Now roll your clay/compost/seed mix up into little balls about the size of ping-pong balls, and set them aside to dry

When you are ready, start spreading the floral joy!

ps. The wildflower meadow pictured here was at Hever Castle in Kent, UK. The children and I spent an afternoon there (can you spot Ralph, then aged four, racing through the flowers in the photograph above?) and it was every bit as heavenly as you’d imagine it to be.

Ten days of illustrations

I’m just past 10 days into the #100DaysinDinan project, and so far I am loving it! As I had hoped, taking out the time to draw these pictures each day is taking me back to our time in the village, and how it has influenced me and my family in big ways and small.

To jog my memory and find things to paint, I’ve been scrolling through photos in my camera, and that has been an extra-welcome trip down memory lane. The children love to see what I’ve been painting each day, often chiming in with “Remember when…?” as they hold the little cards in their hands.

I’m making the envelopes for each card by tracing one of the original envelopes the cards came in, onto used calendars and magazine pages. A stamp or two, and the address: there’s not much room for anything else, so into the post they go.

Here are the first 10 that I’ve painted and posted, with a bit of the back-story behind them.

hotel de beaumanoir

The beautiful, 15th-century archway to the former hotel de Beaumanoir: 1 rue Haute-Voie, Dinan. This was just around the corner from our apartment and after dropping off our bags on Day 1, we took a wander through town. This intricate stone archway took my breath away, and I couldn’t believe I was going to live in such a place

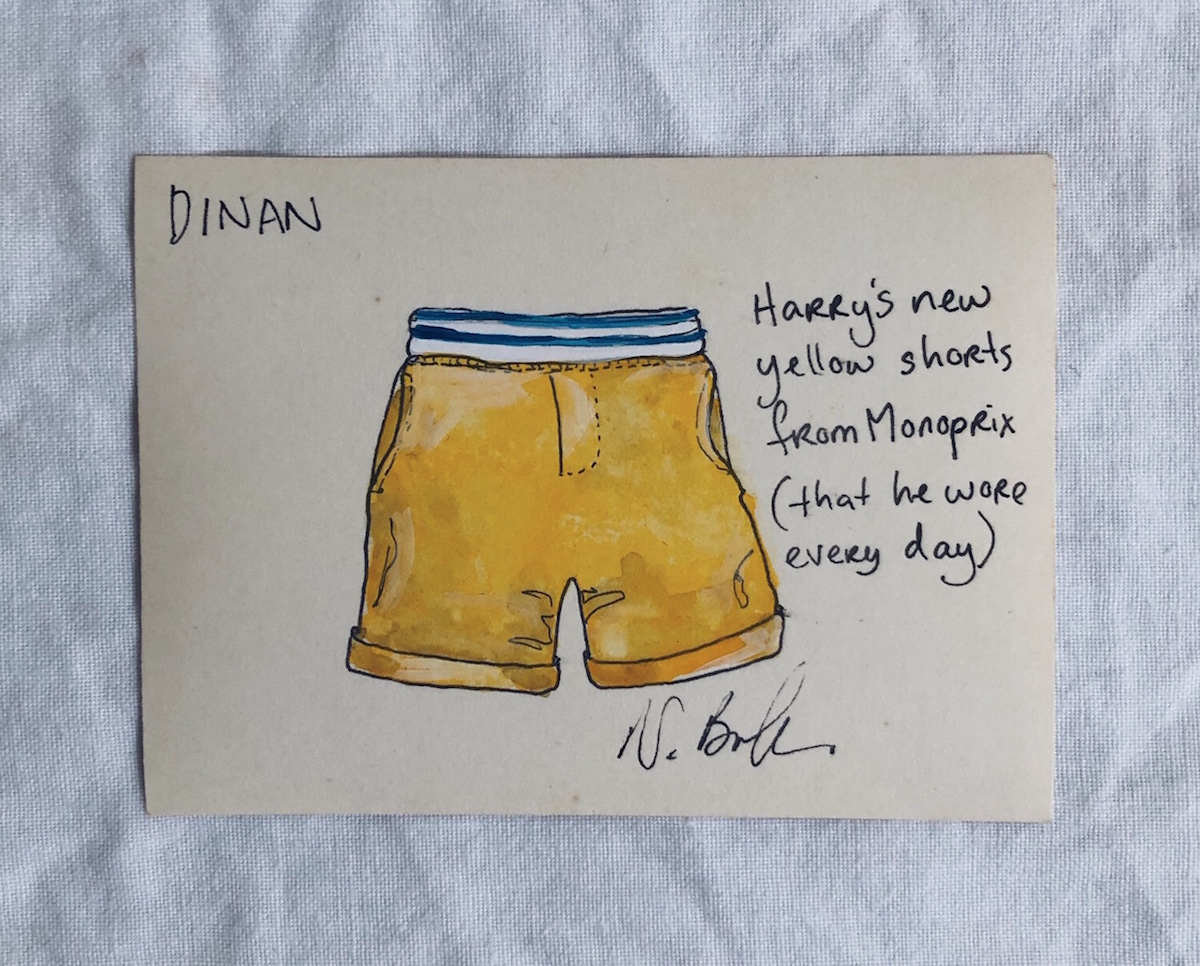

new yellow shorts

We arrived in France from the coldest month of winter in Australia, with very few summer clothes in the suitcase as the children had already grown out of theirs from six months earlier. While riding the carousel in the hot sun the day after our arrival, four-year-old Ralph found his jeans just - too - hot. I popped into the Monoprix and bought him these sweet yellow shorts, which he loved so much that he wore them nearly every day until the end of summer

maison bazille

There are several chocolatiers in Dinan, and we sampled them all! Our favourite was Maison Bazille on 10 Rue de l'Apport. Partly for the silky homemade chocolate (made on the premises) with all kinds of flavoured ganache, and partly for the macarons, but mostly because Anne, the proprietress, was just so lovely. She would welcome us with beaming smiles, and when we returned after three weeks in the UK, she gave the children cuddles and kisses. We would slow down every time we walked past, in order to catch her eye and wave

half-timbered houses

Dinan is famous in France for the half-timbered houses that line its streets. They are crooked and wonky, because when they were built (mostly the 14th and 15th Centuries) there was a tax on floor-space at the ground floor, so people built small at the base and increasingly spread out as they built up. (This particular house is now a restaurant, La Mere Pourcel on 3 Place des Merciers. I really wanted to eat there but it looked too fancy for a mum and two kids, so I’ll have to go next time!)

moules-frites marinieres

Ralph was gung-ho with the moules-frites from the very beginning, but Scout only discovered them during a visit to Mont Saint-Michel. It was a steaming hot day, and we sheltered from the sun in a restaurant for lunch. I’d ordered myself a bowl of moules-frites while the children had pizza, but Scout ended up stealing more than three-quarters of my mussels. We told the proprietress they were the best we’d ever tasted, and she smiled and shrugged, “c’est la saison” (it’s the season)

rampart towers

There are lovely little towers in the castle walls all the way around Dinan. This one is over one of the steep streets that lead between the hilltop part of the town, and the ancient river port. The children and I would walk along the ramparts on the way home from school, and stop to take in the view from the top of this tower

the padlock letterbox

The steep, cobblestoned rue du petit fort leads all the way down to the river at Dinan, and the whole way down the little street is lined with ancient and fascinating homes, shops and cafes. This door is almost at the bottom, and boasts the biggest padlock you have ever seen, which now does duty as a private letterbox

sea-birds

Dinan doesn’t feel like a seaside town. There is a river, to be sure, but it no longer dominates the landscape or trade, ever since the town moved up the hill and behind the castle walls for safety, many hundreds of years ago. But this is the west coast of Brittany, and the sea is still close enough that sea-birds call and circle in the morning, and wander through the streets hoping for scraps from tourists at lunch

boats on the canal

The river Rance, by the time it gets to Dinan, is little more than a canal. The first week we arrived, we took a ride on a river-boat up the canal to the neighbouring town of Lehon, the children fascinated when we had to stop at a lock and wait for the water to rise. There was a path beside the canal where horses used to walk and pull the boats. Once, a family’s horse sadly died, so the captain’s wife had to ‘harness up’ and pull the boat herself. There are photos. In the summer, weekender boats like this one I’ve painted would chug past and we’d wave at them

birkenstock kilometres

The day before we left on our adventure, we took the children to the Birkenstock store in Melbourne and picked up a pair of sandals each. It was winter here in Australia, and they had long grown-out of their sandals from the previous summer. When we arrived in France, those sandals became synonymous with the new sense of adventure and resilience my children developed. From complaining about a two-block walk in Australia, they cheerfully walked 10+ kilometres every day in those sandals

Tiny missives: 100 days in Dinan

It has been way too long since I hosted a postal project, but all that’s about to change.

Do you fancy receiving a tiny painting on a tiny vintage card, in the mail? I’m making 100 a day, starting this week, and would love to send one to you, my friend. Here’s the story…

Last month while we were in Paris, my family and I took a walk beside the river to browse les bouquinistes. You’ll have seen them I’m sure: the little green-box riverside markets that flank both banks of the Seine. They sell secondhand books and paper ephemera, and have been doing something similar, I believe, since as far back as the 16th Century.

We had left our village of Dinan the day before and I was looking for vintage postcards from the region, but then I saw these: tiny packets of photographs that tourists used to buy and carry home with them, from the days when cameras were rare and printing photographs was costly. Most of the packets were, I’m guessing, printed almost a hundred years ago, or at least some time between the first and second World Wars.

And as I turned them over in my hands, sniffed that old cardboard (is there anything better than “old book” smell?), I knew I wanted to give them life.

I’ve spoken in the past about how I believe postcards and other tourism souvenirs were made to travel and to be shared. The journey is the entire point of their creation. And yet so often, a postcard can sit unsent and unseen in a shoebox for years, or even decades. In 2017 my husband bought me a box of 1000 unused vintage postcards (most of them fabulously ugly), and I posted them to strangers and friends alike, all over the world, for the whole year. We called this the Thousand Postcard Project. A little while before that, we found some books of antique postcards and I sent those out too, then made miniature envelopes out of the tissue paper that separated them, and posted haikus into the world.

So as our little family all stood together in Paris, with the winter wind in our faces and the children moaning “Come on this is boring” because we were supposed to be en route to the Christmas markets, those tiny cards were calling to me and I couldn’t resist. I asked the bouquiniste, “How much for nine packets?”

Later, I wrapped the miniature postcards in a scarf and carefully stored them inside the heavy 18th-Century writing box I’d picked up at the flea markets in Dinan (which was in turn nestled inside my suitcase, wrapped in rain-coats and stuffed all around with socks to protect it from bumps and bashes, and which I carried around for an entire month while we travelled), and promptly forgot all about them. This made for a lovely surprise when we finally returned to Australia, and I began the arduous process of unpacking after five months away.

Since then I have been pondering what to do with them next, and today I have decided! I will use them as tiny touchstones that will link me back to the time I spent in our French village: to the small and precious moments we shared, and the little lessons (and big lessons) we learned.

The challenge: 100 days in Dinan

I have exactly 100 of these vintage or antique cards, each of them depicting a place or a moment from somewhere in France. So every day for 100 days I will take out a card and draw or paint something simple on it that illustrates our time in Dinan. (If you want to follow along on Instagram, I’ll hashtag #100daysinDinan whenever I share a picture).

It could be as grand as a castle or as simple as the tomatoes we picked up at the markets but, as I paint, I will be remembering the sunny day we visited that castle, or the way those tomatoes tasted, sliced onto baguette and sprinkled with salt.

Cumulatively, I hope the painting of these 100 cards will help take me back to Dinan in my heart, and help to keep alive some of the slow and precious lessons I learned during our time there.

The community: 100 tiny missives in the post

But that still isn’t setting the little cards free, is it. So the second part of this challenge is where you come in. Every day after painting a card, I will slip it into a handmade envelope and post it anywhere in the world.

Would you like one?

If you would, simply fill out the form below to share your address with me. This is all about community and for me these sorts of projects are sweeter for the sharing, so you don’t need to pay anything, join anything, sign anything or respond in any way. Just accept my thanks for being part of this little 100-day project.

The form will stay open until I have 100 addresses but, right now, I’m off to start painting!

UPDATE: I now have all 100 addresses so I’ve removed the form for this project. If you missed out, I’m sorry!

If you’d like to hear about my future projects first, you can subscribe to this blog using the box below, or subscribe to my monthly newsletter using this link. I also share what I’m doing on Instagram, and you can find me at @naomibulger.

The truth about what happens on our walks

Chevalier Ralph clambered up onto the rocks by the path, to his look-out. “Can you see the advance guard?” the Warrior Queen Scout called up to him, “Are they close yet?”

We all peered through the forest trees and across the canal, to the hiking trail on the other side. Two retirees carrying trekking poles were striding along the path. “I see them!” yelled Chevalier Ralph. “They’re almost ahead of us!”

And then at the same time, both children looked further into the distance, and stiffened. A walking group of about 20 more retirees had rounded the corner of the path across the river, behind their two ‘advance guard’ friends.

“The pack! The pack of oldie chevaliers!” the children yelled, in mock terror. “Run!” And so we ran, a mad race to the old castle ruin, us on one side of the river and our unwitting enemies on the other.

We were two chevaliers and one warrior queen, you see, and we alone knew of a plan by our arch enemies to attack our castle. They intended to sneak up on the castle, cunningly disguised as an innocent-looking walking-party of octogenarians, then storm our walls and take the kingdom.

Luckily, we happened upon them during our walk. Now it was up to us to get to the castle before them, and save the day.

We raced along the forest path, past the ancient abbey with scarcely a glance, and scrambled up the steep hill to our fortress, all the while listening for the sound of deceptively-benign conversations about chestnuts and knitting and grandchildren.

Once there, we pulled up the imaginary draw-bridge, locked the non-existent gates, and armed the crumbling battlements. Hastily (there was no time to lose!), we reached into my backpack and added to our number: the castle was now under the protection of Chevalier Ralph, Chevalier Mummy and the Warrior Queen, as well as a soft toy Lightning McQueen, another soft toy Harry Potter, and a little plastic dog from Paw Patrol, called Chase.

The toy chevaliers protected the most vulnerable aspect of the walls, overlooking the valley, while the three of us checked every other side, craning our necks for enemies disguised as grandparents. We sent messages via carrier pigeon to the next town over, warning them of imminent attack.

At this point the Warrior Queen decided she was no warrior after all, but just a plain old queen who needed protecting. After about five minutes of that she found that being helpless was boring, and so miraculously developed the powers of flight. A man wielding a leaf-blower in the village below was actually a dragon, roaring with fury and spewing dust and leaves.

Chevalier Ralph stopped bing a chevalier and became instead a superhero, by the name of SuperBoy. As we headed to the neighbouring village, we had to stop multiple times for SuperBoy to throw stones into the canal, as this was the only way to recharge his waning superpowers.

Soon after this, the adventure grew so complex that it is impossible to explain. Suffice to say we won the day, both sides of the war agreed to make friends, and we celebrated with chocolate eclairs and raspberry tarts on the way home.

Listening & noticing

We first noticed it on a Saturday night at the beginning of September: the unnatural quiet.

We were returning from the playground, where the children had spent a rousing hour-and-a-half making friends via a game of Ralph’s invention. It involved tossing his soft car-toy into the midst of a group of children who were spinning at top speed on a merry-go-round. If they managed to catch it, they’d toss it back, causing gales of laughter as Ralph ran hither and thither to pick it up like an eager puppy. Over time, the game evolved into chasings, with everyone chasing the one person who held the car, which they’d then pass to someone else if the mob of children got too near. A bit like under-six football, only with a lot less rules.

The children’s French language skills are coming along swimmingly, too. Mid-way through the game Ralph took a break in order to run up and tell me, “A girl said ‘bonjour’ to me, so I said ‘bonjour’ back.”

So, practically fluent.

We left the playground and sat down at a table outside a restaurant in the heart of town. I ordered us a tuna salad to share, and a glass of wine for me, and leaned back to enjoy the evening. That’s when I noticed it: the quiet. The town, which we had left two hours earlier bustling with the now-familiar throngs of thousands of tourists, buskers, market stalls and families, was now all-but empty. Two old men at a table nearby, smoking over pastis. The woman from the Presse across the square, leaning in the doorframe of her shop and watching the dusk. An old English sheepdog, asleep on the flagstones.

That was pretty much it, other than us, and it felt uncanny, to say the least. I said as much to the woman who brought us our salad. “Oui,” she said, her face widening into a broad smile, “c’est tres tranquil!” (“Yes, it’s very quiet!”). In the space of one afternoon, the school holidays had ended, and the crowds had melted away like mist in the sun. Now, I thought to myself, I am about to discover what life is really like in the village.

And one great lesson I am learning from life in this village, now that tourist-season has closed, is that there is a time and a season for everything, if only we learn to listen for it.

At first this felt restrictive because, in Australia, we are used to doing all the things, all the time. We eat when we can (hungry or not), and often on the go. We work all the time. Early morning. Late nights. Weekends. My husband brings his computer, iPad and telephone with him on holidays. We do our shopping at odd hours, slotting it around our long days. Pick up this on the way home from the office, grab that on the way home from school, shop for those at 9pm on a Sunday night, and order the rest online at 1am on a Tuesday after finishing a deadline.

I get my coffee take-away and eat at my desk, and our mealtimes are likewise scattered. For breakfast, Mr B grabs a banana for the car and snacks at work when he gets hungry. Often I forget to eat lunch and then pick at unhealthy anythings scavenged from the pantry all afternoon. I feed the kids their dinner and put them into bed, and then by the time Mr B gets home from work I’m often too tired to cook again. We are keeping Uber Eats in business.

By comparison, this is our life in the village:

* The church bells ring at seven in the morning. They don’t start earlier and the inference is, what person in their right mind would get up before seven in the morning anyway?

* On church-service days (including weddings and funerals), the bells start ringing 12 minutes before the hour, and continue all the way up until the hour, to give everyone in the village time to get to church

* The markets run from eight until one on Thursday, and that’s where everyone in town stocks up on fresh fruit, vegetables, meats, fish, cheeses and spices for the week. It’s seasonal, and you just have to roll with what’s growing (no California oranges or New Zealand kiwis here)

* The cafés and restaurants open at noon until about two for lunch, and seven until nine for dinner. Outside those hours most are closed and even if they do open, you can only get drinks

* I’ve yet to see a take-away coffee cup

* The shops don’t open before ten each day, and they are closed on Sundays and Mondays. “Sundays are family days,” my friend told me, with an expressive gallic shrug that seemed to add, “naturally”

As you can imagine, we came unstuck at first. I used up the last of our milk on a Saturday night and shock! horror! Had to wait until after ten on Tuesday morning to buy more for my tea. More than once, I failed to buy enough fruit and vegetables at the markets and had to go without for the rest of the week. (Going without is better than facing the prospect of picking through the genuinely-rotting ‘fresh’ produce in the local supermarket to find something edible. I’m not kidding: if the supermarket was a cartoon, there’d be little wiggly smell-lines wafting above it).

When we first arrived, my kids’ little tummies were used to having lunch at eleven or thereabouts, and we roamed fruitlessly from café to café, searching for something that was open before noon. We had the same problem when I wanted to take them out for dinner, but nobody would serve food until after their bed-times.

But as time has gone by we have slowly adjusted to these new rhythms and, somehow, they are beginning to make profound sense.

I take menu inspiration from what’s fresh at the market, rather than arriving at the supermarket with a ready-made list and very little idea of where my food is coming from. When it’s time for coffee, I take five minutes to sit at a cafe and people-watch while I sip, noticing and appreciating the taste… and the moment of peace.

Mealtimes are for proper meals, and we enjoy them thoroughly. But when mealtimes are over, we stop eating. I don’t snack any more, and I’m noticing the difference to my waistline. Sundays, when all the shops are closed, are for big cook-ups for the week ahead… or for long walks and picnics if the weather is just too good to resist.

It feels as though we are training our bodies to notice the rising and setting of the sun, the rhythms of the harvest, the turning of the globe and the changing of the seasons.

I am storing these life-lessons away, tucking them into my suitcase alongside the souvenir biscuit tins, vintage ceramic jelly mould and new winter coat that I also picked up here in France, in the hopes that they can be woven into my daily life when we return to Australia.

One day in Paris (with small children)

Brace yourself: your day will probably have to start with the Paris Metro. Hold on tight to their hands, try not to inhale too deeply, and, if it’s peak hour, leave enough time to allow a few over-crowded trains to go by before you venture on in (here is a fun guide to surviving the metro in Paris).

Be a tourist

Take the Metro to somewhere close to a tourist attraction. I know, I know, you’re cooler than that. You want to explore off-the-beaten track alleyways and hole-in-the-wall one-dish-only Michelin star restaurants only Parisians know about. But you only have one day, and you are travelling with small children. There’ll be places they’ve seen in movies or read about in books that they are just desperate to visit. My friend, you are going to the Eiffel Tower!

The goal is that you emerge from the dark, smelly Metro-cesspit and watch your kids’ eyes grow wide and hear them breathe “Wow!” as the true beauty of Paris rises all around them. That “Wow” is worth a thousand super-cool secret bars, trust me.

Depending on which part of the city you’re staying in (i.e. the most convenient Metro lines to you), you could aim for any of these Metro stations:

To see Notre Dame first: get off at Saint-Michel Notre Dame (RER lines B or C), or Cité (pinkish-purple line)

To see the Louvre Museum first: get off at Louvre Rivoli or Palais Royal Musée du Louvre (yellow line), or Chatelet Les Halles (RER line A)

To see the Eiffel Tower first: get off at Champ de Mars/Tour Eiffel (RER line C)

To see the Arc de Triomphe first: get off at Charles de Gaulle Etoile (yellow, blue or aqua lines, or RER line A)

To see the Opéra Garnier first: get off at Opera (olive, pink or purple lines), Chausée d’Antin La Fayette (pink or lime lines), or Auber (RER line A)

To see the Tuileries garden and Place de la Concorde first: get off at Tuileries (yellow line)

Buy a croissant

Get yourself out of that Metro station, and look around. Wherever it is you emerge, it’s a fair bet it will be beautiful! Let the kids stretch their legs, and take a ramble over and around wherever it is you’ve decided to start. (For my kids, this means racing around the forecourt at The Louvre).

Now find a nearby cafe and prepare to overpay outrageously for a coffee and a croissant. It’s worth it. The kids are hungry, and you’re in Paris. Order them a pain au chocolat and they will be over the moon. (Remember to use the loos here because you’re going to hit the road again soon).

Hop on a bus

Look around for a hop-on-hop-off bus and buy yourself a day ticket. These buses are a fantastic way to look around a city if you don’t have much time. They hit all the top tourist destinations and the name pretty much says it all: you can hop on or off all day, using these buses to make your way around the city.

If you’ve emerged at any of the places I listed above, a hop-on-hop-off bus will be nearby, so just grab the next one: this is how you’re going to get around for the rest of the day. Sit upstairs if the weather is fine.

Especially if your children are quite young, the hop-on-hop-off bus will work with their moods. Do their little legs need a rest? Hop on the bus and drive around, seeing the sights while giving them a break (bring snacks if you need to). Are they growing restless? Jump off at the next stop and let them explore - another bus will be along whenever you need it to continue on your journey.

Let the kids set the itinerary

Now let the kids set the itinerary. As you drive past the bouquinistes (those green market-stalls along the Seine), tell them about the antique postcards and books and trinkets they can find there and, if they like the sound of that, get off at the next stop. If Notre Dame fascinates them, hop off there, then take a walk to Shakespeare and Company afterwards. Or if they are art-lovers, hop off at the Musee d’Orsay and visit all those lovely impressionists. (Notre Dame tip: you can book online to climb to the top and skip the lines. Musee d’Orsay tip: book your tickets online to skip the queues).

Climb that tower

Let’s face it, assuming you do let the kids take charge, at some point or another today you are most likely going to the Eiffel Tower. (If you definitely know they’ll want to do this, try to make the Eiffel Tower your first stop, because the lines only get longer as the day goes on).

Hop off the bus, and prep the kids. Tell them that yes, they can climb it, but it is a long way up, and there’s no changing their minds half way. Would they prefer to take the lift? (If you like, you can buy a ticket that allows you to walk up to the first level, then take the lift to the second. You can choose to take the lift back down as well).

Half an hour later, ask incredulously, “Are you sure??” when your 4yo and 6yo declare that they want to climb both levels. Now moan and pant behind them as they set a cracking pace ahead of you, and you follow as best you can, carrying all the bags and coats they shed along the way. Have a tarte au pomme or a hot chocolate at the top. You’ve earned it.

(Let them buy that crappy Eiffel Tower snow-globe keyring. You are making memories.)

Take a break

When you need a break from exploring, hop off the bus near one of Paris’ many beautiful parks. Take a breather here, and let the kids race around if they need to, or lie in the grass and make shapes out of clouds if that’s more your speed. If the weather is hot, float a paper boat in a pond, or let them dance through sprinklers to cool off.

Optional extra: after receiving a thorough soaking from the sprinklers, allow them to treat you and half-a-million other tourists to a dance performance on the Trocadéro to dry off. (Oh yes, they did). Or bring a change of clothes.

Ride a carousel. Buy crepes from an outdoor vendor and eat them for lunch under a tree or beside the river.

Ice cream

Hop back on the bus, and visit as few or as many more sites as you want to. When you’ve had enough, hop back off at Notre Dame, and take a short walk along the Seine and over the bridge to the picturesque Ile St-Louis, to enjoy a cone of the best ice cream in Paris, from Berthillon. It’s seriously worth it. Sit in the gutter if you have to. You’re not shy.

Have dinner with the artists

How is your energy? Are all of you flagging? If you have the stamina (or if you have a spare morning the next day), take the Metro once again, up to Montmartre.

The closest stations are Abbesses (green line), Anvers (blue line) or Lamarck Caulaincourt (green line). If you’re not sure which way to go from the station, just head up hill. Depending on which direction you come from, you’ll either pass winding lanes with artists selling wares that spill out onto the sidewalk; or there’ll be buskers, hawkers, tricksters performing that old cup-and-coin trick, and way more pedestrians than cars. Each walk is equally fun.

At the base of Sacre Coeur is a carousel that (joy of joys!) has two levels. This will make your children very happy indeed. When they’re ready to leave it, take the funiculaire up to Sacre Coeur (go in or not depending on their interest - it’s the actual funiculaire that they will love, and the cost is a standard Metro ticket price).

Now walk around the corner to Place du Tertre for dinner. Choose one of the restaurants facing onto this lovely public square (once a favourite haunt of all your favourite artists) and order something delicious. I love moules-frites with a crisp rosé, but you do your thing.

There will be loads of amateur artists wandering around, offering to draw or paint or cut portraits of you and your little ones, and selling landscapes of all the places you have visited and admired today. I know, it’s cheesy, and the likeness is not exactly the best. But what a great memento of your day in Paris with your family, having your children immortalised forever in the style of a mid-century-mod portrait. You could take a wander around and pick up a souvenir for not too much if you like, or settle in for that dinner and let the artists come to you.

As dusk settles and the café lights come on, snuggle those tired kids onto your lap and ask them, “What was your favourite part of today?” They’ll tell you it was the ice cream, and the sprinklers. Stuff you could just as easily have done at home.

Pilgrims

The day started at 2:42am, with a blood-curdling scream issuing from the children’s room. I barrelled in, stubbing my toe on the dressing table then tripping over the low bed they share, to discover Ralph sitting bolt upright, in the aftermath of a particularly bad dream. He was trembling, so I held him and kissed him until he calmed down.

When at last he lay back down on the pillow, he fell instantly back to sleep. Scout rolled over, kissed the back of his head, and wrapped her arms around her little brother to keep him secure. “Ralph, you are lucky to have such a loving sister,” I said. Scout whispered into his curls, which were still damp with perspiration from the nightmare, “I am lucky to have him.” And then she, too, sank back into sleep.

By the time I made it back to my own bed, I was so full of adrenalin it took forever before I found my own way back into slumber, and it felt like only minutes before the charms of my alarm woke me again at 5:30am. I groped through the dark a second time, this time on tip-toe, to put the kettle on in the kitchen, prepare breakfast for the children, and pack a lunch for the day ahead.

An hour later, the three of us were creeping through the still-dark village, whispering so-as not to wake the locals. It was like a magical other-world in that pre-dawn dark: cobblestones shining under the orange lantern-light, and not even a whisper of a breeze. It felt, truly, as though we had stepped back in time. I was thinking this to myself as we tip-toed toward the bus-stop, and then Scout said to us, “This morning, the town belongs to us.” So I guess she felt some of the magic, too.

We made it to the bus-stop five minutes early. And stood there shivering in the dark. I put my arms around the children and Ralph said, “You are our mother-hen.”

Time for the bus, but no Line 10 to be seen. We waited a little longer in the dark, watched other buses come and go, shivered a little more, cuddled a little more. I pulled the timetable out of my bag and checked again: yep, I had the days right, and the times. We wandered over to the bus-shelter at the other side, to read the same timetables that were pinned to the wall…

… only, it turned out they weren’t the same timetables. I looked up at the wall again. Turns out, the bus-times changed when the calendar changed, and our bus had rolled away five minutes before we had arrived (probably right about the time Scout had said, “the town belongs to us”).

“There’s another bus in two hours,” I told the children. “We could take that? It won’t get us all the way but we could at least go to the beach.” They took it well, the excitement of the early morning and the walk in the dark still pumping in their veins, and didn’t even want to go home in the meantime. “Let’s just wander around,” Scout pleaded, but even I have my adventure limits, so we turned for home to pass the time until daylight.

(We had a win on the way back: our boulanger was open. By way of compensation, I bought them each a pain au chocolat, still warm from the oven, and picked up a baguette to add to our picnic later on.)

Using the Internet back home I discovered we could cobble together trains and buses and make it to our original destination only an hour later than planned, so out we trundled again an hour after that, ready at long last to begin our pilgrimage.

Walk. Train. Wait. Bus. Walk. And then another walk, a long walk, in the sun. The children were disappointed: they had hoped to risk the tides and wade through silt and sand to reach the island, but it turned out that a perfectly crafted boardwalk unfolded ahead of us, and our pilgrimage felt a lot easier, and more sanitised, than we had envisioned.

But the heat had become searing, and a long walk, when you are only four years old and had an early morning with multiple mishaps and the sun is bearing down on you, can quickly become arduous. We tramped on, at what felt like a snail’s pace (aka Ralph’s pace), feeling as though we were making more authentic, pilgrim-esque, effort with every step.

And then, carrying softly across the sand amid the chatter of thousands of other wayfarers, the noon-day church bells began to ring. So we marched onwards with renewed vigour, following the call.

Inside, I had been hoping to find ghosts. I’m good at finding ghosts. I can find the magic in even the most touristy of places, if once there was true magic. (Like Notre Dame, for example, where I once filed in with a million other tourists but still managed to still my soul and feel the prayers, hundreds of years of prayers, fluttering toward the cathedral ceiling like a million butterflies.)

But as we strode over the drawbridge and under the portcullis and filed into the medieval village, packed shoulder-to-shoulder with what felt like every other tourist in France, the ghosts were silent. Scout and I shared a big bowl of moules frites (Ralph had pizza), and then we rejoined the throng on the climb up the hill to the abbey. Poor Ralph tripped over on the pavement and almost got trampled by a German tourist and his dog. We dusted him off, dried his tears, and carried on. A few minutes later, he bashed his head on a flying buttress. We crammed against a wall and tended to him again, kissing the forehead where a lump was rapidly rising, but my little champion rallied and we resumed our climb. Several flights of stairs - me holding tight to Ralph’s hand to stop him stumbling - and we made it to the top mercifully without incident.

There, at last, the crowd thinned. We all three took a breath, opened our arms to the breeze, and discovered that we were, in fact, on top of the world.

I had been hoping for the ghosts of the past but what I found instead were spirits. Soaring, swooping, invisible and yet profoundly present. Open-armed, open-hearted, open-minded.

On our way inside the abbey, Ralph fell in the gravel and skinned his elbow and both knees. But he got up, and carried on. Heading home, now in searing heat, we discovered the lines for the horse-drawn carriage I had promised them, and also the more mundane but infinitely more practical buses, were so long, we’d never make it back to our bus and the last train on time.

I looked at that boardwalk, stretching out in front of us, and then I looked at my beautiful children, already drooping and exhausted. I didn’t know what to do. “I don’t know what to do,” I said. The words escaped me before I could stop them.

“We can walk Mum,” my little champions assured me. “Don’t worry!” I grasped both of their hands and began to power-walk, the two of them trotting along either side of me. Stress prickled me on the inside. The signpost said the walk should take 45 minutes: at Ralph pace, that meant at least an hour and a half. We had half an hour.

I’m not going to lie, that was a rough half hour. When Ralph fell yet again, I almost thought we were done-for. But those valiant children carried on. We made it to the bus with less than a minute to spare (I’m not kidding: the bus-driver was closing the doors as we stumbled up, sweating and panting and pleading), and both children wilted like flowers into their seats.

In all, they walked 14 kilometres in aching heat, and 14 kilometres in the heat is a long, long walk for two little children, not to mention the numerous bumps, bruises and grazes picked up by Ralph along the way. My heart swelled for them. Pride, joy, mother-guilt and love all mingled together at the way they had carried on forward, not complaining, in all that difficulty.

And then I thought about the air at the top of that abbey, and the way the wind had unravelled across the sandy flats to the sea with heart-stopping freedom, and how those same weary children had opened themselves to the wind with such enthusiasm that it was infectious, their evident joy and laughter spreading to the other tourists around them in smiles and giggles and sighs.

And then I thought about spirits, soaring.

The magic beach

There are cliffs at the edge of the horizon, behind the rocky island, so pale and misty they could be a mirage. I wonder aloud at what point the coast curves around, until somebody tells me that no, that is Jersey. The day is so clear that we can see all the way to the British Isles.

We arrive just as the tide is drawing out, unaware of how lucky we are. Long stretches of golden sand, still rippled with the marks of the waves, unfold under our feet. We explore rock-pools, a waterfall, an infinity pool built into the ocean wall. Gingerly we step between barnacles and in and out of patches of seaweed, making our way to a fort and prison on a hill. (Only a few hours later, there will be no beach at all, and the fort will become a wave-battered island.) Here are ancient walls, hidden rooms, and breathtaking views across to the castle walls and the old town.

I picture all of this under water in only a matter of hours. The paths, the steps, the hewn-stone alcoves... and then I think about Atlantis, and I wonder...

The children start the day in long pants and jumpers and slowly shed layers as the sun grows in strength, ending up gleefully racing across the sand and through the shallow waves in just their underwear. We plan to visit for two hours and stay for seven instead, barely making it to the last bus home, tired, sunburned, and overflowing with happy memories.

As if to complete the cliché, seagulls circle above the castle towers, calling. I feel joy.

Pirates! For centuries, the treacherous coastline, hardy sailors and impregnable castle walls made our magic beach a haven for pirates. Think of every swashbuckling Treasure Island story you have ever heard: yo ho ho and a bottle of rum, and all the rest. Ruthless crews would lay in wait for English, Dutch and Portuguese ships carrying gold, spices and other precious cargo from the Caribbean, then hide their treasure away in the many secret harbours and hideaways that pepper the cliffs and coves. In the 17th century the King of France legalised the pirates (for a share of the profit), and so they became known as corsairs, privateers pillaging on behalf of the Crown. They were so feared that British mariners called our beach 'the Hornet's Nest.'

Ralph chooses a random spot in the sand and starts digging. "Soon I'll find treasure," he announces, with supreme confidence.

This is a place rich in history and beautifully, sometimes brutally, ruled by nature. As we clamber over the still-wet rocks, Scout starts chanting to herself softly, "At our beach, at our magic beach..." from a well-known children's book we have at home. The book is about a beach that is beautiful and magical in its own right but, on every second page, the children in its pages imagine something more: knights battling dragons; an exhilarating underwater race on the backs of seahorses trailing pearls; smugglers, sneaking along the rocks at dusk.

The book is called Magic Beach.

Summer picnic

We spread out our blanket in the shade on the grassy flat inside the ruins of the castle. All around us, birdsong. The paper-rustle of the breeze in the trees. The occasional, distant hum of a car bracing itself to climb the hill on the other side. And centuries. The sound of centuries. The vibrations of a thousand years, deeper than human hearing but as real as that bumble-bee we saw, drunk on pollen, staggering from borage to blackberry and back again.

I take off my shoes and the grass is soft and warm beneath my toes. I want my body to touch the hum of the centuries, to see if they will touch me.

"Are you grounding, Mummy?" asks Scout. That's my girl. The children kick off their shoes, too, and race about amid the wildflowers, shooting corks at each other from toy wooden crossbows. We pick flowers to press and, when the sun gets too hot, retreat into the shade for lunch. It is simple fare, but so, so good. Baguette from our favourite boulanger in town, soft cheese, pear and apple. And because I am still not entirely French, a thermos of hot tea.

I stretch out on my stomach, kicking my bare feet in the air behind me, and read to the children aloud from Lunch Lady magazine. A story about the romance of caravanning in Australia. Scout says, "Let's stay here for the whole day," and I agree. Ralph discovers he can carry the corks for his crossbow inside the fat curls on his head.

There is a plaque set near one of the ruined towers of the castle, that tells a little of the history of this place. It is uncharacteristically poetic for a plaque, and so beautiful that I search the small-print for an attribution of some kind. I feel as though I'm reading Victor Hugo, or Walter Scott, rather than someone from the Bretagne Tourism Office, circa nineteen-eighty-something.

I'll share some of it with you.

"For over a thousand years, the mighty castle walls dominated the banks of the river and echoed to the clash of iron and the cries of warriors. Now all is quiet on the deserted peak. Nothing is to be heard but the songs of the shepherds and the birds. The old feudal giant is nothing more than a meagre skeleton and each winter carries off a fragment. Only brambles and wild flowers inhabit the gaping ruins. Corn and apples ripen the orchard that once was a place of arms. Only the dew from heaven and the labourer's sweat now water this earth which warfare once drenched in blood and tears."

Early morning with a teapot clock

There is a ticking clock. I followed the sound of it this morning as I tip-toed barefoot into the kitchen in a dark that was almost complete, aside from the soft, orange glow of one streetlight in the leafy square down below, filtering through the window. Tick tock. I tilted my head to listen more closely, and groped about in the dark for the object that was ticking. Held up to the faint light of the window, it revealed itself to be small, ceramic clock shaped like a teapot, and it said 5:40am. Good enough for me. I put the ticking teapot down, flipped the real kettle on, and opened the window to let the cooler air in.

With my tea made, I sat down by that window and looked out over the square: there is an old church from which last night a choir of angels filled the air with song; a half-timbered medieval house across the way; and cobblestones around the silent square which, during the daylight hours, is bustling with people drinking and dining and laughing and smoking and talking: talk, talk, talking in snatches of French that I pick up here and there as they waft up to me in my third-floor eyrie, and it feels impossible that I am actually here.

I think about this as I sip my tea. I want to take this opportunity, before the rest of the house is awake, to let the reality of this new life sink in.

We have moved to France. Not forever, but for a fair bit longer than your average holiday. It is August right now, and we won't be home until New Year. We have an apartment in a village, and our goal while we are here is to simply and whole-heartedly immerse ourselves in life. We want to explore every inch of this village, on foot. We want to practise the language. We want to make friends. We want to eat the food and we want to learn to cook the food.

Our village is pretty. Almost impossibly pretty, like a storybook. I didn't know this when I chose it: I simply googled towns of a certain size in the area we wanted to visit, and shortlisted them according to amenities like nearby hospitals and train stations (the reality of travel with kids). I can't even begin to share the knots of anxiety I had been experiencing in the lead-up to this trip (and oh! the late nights finishing my deadlines!), and the journey here took two days and was genuinely gruelling. Nobody wants to see a four-year-old with bloodshot eyes from exhaustion, and still have to tell them "Sorry, Mummy can't carry you because of the suitcases."

But yesterday as Paris gave way to fields and forests as our train sped on and on through deepening wilderness, my heart began to lift. Our stop: the end of the line. We clambered off and dragged those heavy suitcases and heavy-lidded children over the rough cobblestones, up and down laneways and in and out of crooked little streets, until suddenly we rounded a corner and an antique carousel was just beginning to turn. A hill beneath it swept down over ancient rooftops peppered with terra cotta chimneys, behind a riot of summer blooms. Pedestrians had taken over the road, the one brave car that appeared every five minutes or so being forced to inch its way tentatively through swathes of people eating ice cream.

Scout turned to me with eyes like dinner plates and said, "Our town is amazing!" and I let out a deep breath I hadn't even realised I was holding.

Our caretaker met us at the door with smiles and keys and a cornucopia of French bread, eggs, milk and fruit that I had asked her to buy for us. (Ralph bit into an apple and then it was his turn for those bloodshot eyes to turn into dinner plates: "It's a PEACH!" he announced, with the joy that can only be had by a fruit-loving boy who only two days ago was in winter, and proceeded to eat two at the same time, one in each hand).

It will take some adjusting. At the moment, we still feel like tourists. The children, with Euros from friends burning holes in their pockets, bought woven bracelets and rings and money boxes and keyrings from market vendors in the streets, and there was no way I was getting them to bed without ice cream first, and a wander through the old streets and through the castle walls.

In two weeks, though, most of the tourists will go home, and we will start to learn what life in the village is like when it is just a village.

The dawn is starting to lift now, and the first of the birds are singing. A friendly cat just launched itself onto the windowsill and frightened the living daylights out of me. When my heart palpitations subsided I said "Bonjour," and it purred a greeting, before slinking off on whatever mission it had originally had in mind.

The clock tower bell is tolling (very considerate: it didn't toll throughout the night, or maybe the bell-ringer just needed a sleep-in today). A few introductory higher notes and then a heavier, centuries old message: dong, dong, dong... seven times. And now I hear seagulls, drowning out the sound of the ticking teapot. Seven o'clock. Time to get the kids up.