JOURNAL

documenting

&

discovering joyful things

A body of work

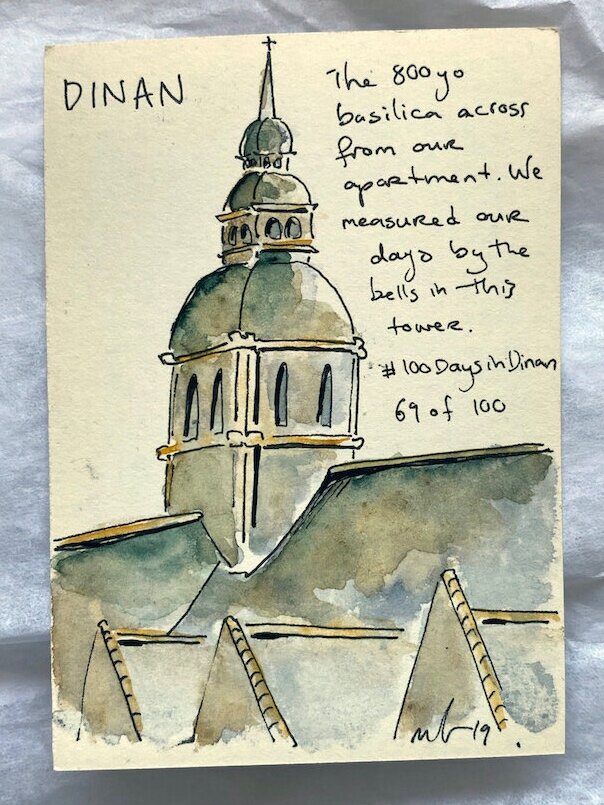

I called this project #100DaysInDinan. One hundred days can feel as fleeting as a week if you happen to be on sabbatical in a medieval French village with your two children. One hundred days pass in the blink of an eye as you watch those children grow (why are their pants too short again? weren’t they in nappies just yesterday?). Although I’m sure you’ll agree one hundred days can stretch out like a lifetime during lockdown.

When I set myself the challenge of illustrating and posting a miniature postcard every day for a hundred days, I hoped to celebrate the memories of our hundred days in France and make them last a little longer. I also wanted to see if I could establish some kind of creative habit that would last me beyond the project.

In the former, I was very successful. Each miniature illustration took me back to a place, a moment, or a conversation: tiny touchstones that helped to keep me connected with those halcyon days. But in the latter, I have to say I was an abject failure. I still wholeheartedly subscribe to the premise of “doing something creative for 20 minutes a day,” which is where I was going when I set myself this challenge. But the reality is that it took me a lot more than 20 minutes - sometimes several hours - to plan out, draw, paint, annotate and sign each postcard, then trace, cut out and paste together a mini envelope, then look up the next person’s address on my list of a hundred addresses and carefully write their address onto a tiny piece of paper and glue it to the envelope, then look up the postage cost online for the destination country and find the right stamps, then affix a wax seal to the back…

Frequently I struggle to find 20 minutes in my day so multiple hours was just too big an ask. That, and of course I’d have to pack away all my paints and papers every time anyone wanted to eat at the dining table (unreasonable family!), only to bring them all out and set up again the next time I wanted to paint. The reality then of my “one painting a day” project was that I’d knock out seven or eight in a weekend by doing nothing else, and then not get to the rest for another month or two. And so time passed.

I sent the last of the postcards to their new homes during Melbourne’s second lockdown, more than a year after I’d started my “100 days” project. The postal services being what they are at the moment, some of them are even taking 100 days or more to complete their journeys across the world. But I kind of like that. It’s fitting, in its own way, that a project that meant so much to me and was such an unexpectedly enormous labour of love would then take its own sweet time to complete the journey. After all, the postcards I was using were 100 years old or more: they had waited a century to be posted, there was no need to rush to the finish line.

And yet as I slipped the final 12 postcards into the red letterbox outside the post office, I did so with a distinct feeling of underwhelm. All that time. All that work! All those precious memories. All those oceans for my postcards to cross. And I was left with… nothing. Just the empty cardboard packets in which the postcards had been stored, locked away for a hundred years or more in somebody’s drawer.

It occurred to me too late that I had actually created for myself a “body of work.” But by posting them all away one by one, I hadn’t let the pleasant weight of creating that work actually settle.

I had been mindfully in the moment, painting each postcard one at a time, reliving the memory it evoked. But moments in life, while individually precious, are also cumulative, each of them drawing on those that came before and forming the scaffold for those that are yet come. (If you look at it this way, a life is a body of work. Or many bodies of work, to be more accurate.)

My miniature paintings were each part of a larger work, tiles in a mosaic, and while I wasn’t necessarily thinking about them in this way as I painted, the idea must have been there somewhere in my subconscious because instinctively I numbered each of them, solidifying their individual places within the one-hundred. They were never meant to exist on their own, and I learned that truth too late. If I had my time again I’d hold the postcards back, painting them all and then viewing them together to see what kinds of stories they told, before posting them back out into the world.

So now, for you but if I’m honest mostly for myself, I am going to retrospectively survey my body of work.

By pulling all 100 illustrated postcards together in this gigantic blog post, using iPhone photographs I snapped before posting (sometimes quite hastily), I have tried to piece together what this body of work might have been. Doing it this way has felt a little bit like an archaeological dig through my memories, once again painstakingly focusing on each individual item, not seeing the big picture until it is finally done, then standing up at last, stretching my back, and surveying the landscape uncovered.

Here it is, my body of work. A hundred days in the living, a year and a half in the making, and for these postcards, a century in the waiting. I wonder what stories it has to tell, when all the pieces are connected together like this? What does it say to me? Where does it take you?

If I learn the answer I’ll let you know.

The time spent navigating memories

It’s a slow process. I don’t just mean the making of the #100DaysInDinan project: combing through old photographs for inspiration, sketching a rough idea onto my antique postcards, going over it in pen, painting it. Then finding old pages from magazines, tracing onto them around the envelopes that had held the postcards for a century, folding them into place, then copying addresses onto paper and pasting them onto the front of the envelopes…

All this takes time, and perhaps in retrospect one a day was too ambitious.

But the real time is spent navigating memories. As I paint I walk my memories like I walked those old, cobblestoned streets, a hundred times over, during the 100 days we lived in Dinan.

As I sketch the outline of a fresh baguette, I am back there again, standing outside Boulangerie Banette with my children, tearing the still-warm loaf into into smaller pieces to share, and the smell is the best in the world: nutty, malty, a hug.

Scout announces, “I can’t go a single day in the world without this bread,” and from that day on, our baker Mohommed keeps one or two baguettes aside for us - and often throws in some free croissants and Nutella crepes - in case they sell out before we get there (which they often do).

Now as I paint I am climbing the steep hill to the castle ruins in the village next door and I can feel the muscles in my legs burning all over again. (And oh! That wicker picnic basket is heavy! Why did I think a picnic blanket was necessary? And did we really need that much water?).

My memories tumble onwards, gaining momentum like my children rolling down a steep and grassy hill on a sunny day, squealing with laughter. I think about the friendly grey cat at the ruins that had so enchanted Ralph. He sat among the wildflowers inside the crumbling castle walls and patted the wild cat while it purred like a tractor, and I dug into the bottom of that heavy wicker picnic basket for the hand sanitiser I was sure I’d packed somewhere. We learned that French cats don’t much mind if your French is somewhat lacking.

I paint my feet in canvas shoes, dangling over the canal on a quiet jetty. As I do it, I taste again the honey and walnut cake I’d baked the day before, and carried with us on our walk. I remember throwing crumbs for ducks that wouldn’t come, and watching the tiny bubbles and rings in the water made by unseen fish coming up to feed.

On comes the summer’s day we spent in nearby Saint Malo, digging and splashing in the beach all day and then running the whole three kilometres back to the bus stop just in time for the last bus home… only to discover the timetable had changed the day before, and we were trapped. So we trudged the three kilometres back into town and found a little hotel. We ate bananas dunked in yoghurt for dinner and it was hot, so hot, so we all slept in our underwear on a big bed. I left the window open all night and watched the moon rise slowly over slate rooftops and terra cotta chimney pots as my children slept.

It slows me. I start with an anecdote but all too soon I am lost in a fully-fledged memory, and follow that path deeper and deeper into the wilds of nostalgia.

It washes over me, a longing to be back inside those slower days once more. I was mindful then, truly mindful, consciously taking in everything: watching it, feeling it, tasting it, and appreciating it. Committing it to memory as best I could, not wanting to miss a thing, not wanting to lose any of it.

So when I paint and I am slow, I don’t mind. A hundred memories is taking me more than a hundred days to record, but this project has become exactly what it set out to be: a process in gratitude.

Ten days of illustrations

I’m just past 10 days into the #100DaysinDinan project, and so far I am loving it! As I had hoped, taking out the time to draw these pictures each day is taking me back to our time in the village, and how it has influenced me and my family in big ways and small.

To jog my memory and find things to paint, I’ve been scrolling through photos in my camera, and that has been an extra-welcome trip down memory lane. The children love to see what I’ve been painting each day, often chiming in with “Remember when…?” as they hold the little cards in their hands.

I’m making the envelopes for each card by tracing one of the original envelopes the cards came in, onto used calendars and magazine pages. A stamp or two, and the address: there’s not much room for anything else, so into the post they go.

Here are the first 10 that I’ve painted and posted, with a bit of the back-story behind them.

hotel de beaumanoir

The beautiful, 15th-century archway to the former hotel de Beaumanoir: 1 rue Haute-Voie, Dinan. This was just around the corner from our apartment and after dropping off our bags on Day 1, we took a wander through town. This intricate stone archway took my breath away, and I couldn’t believe I was going to live in such a place

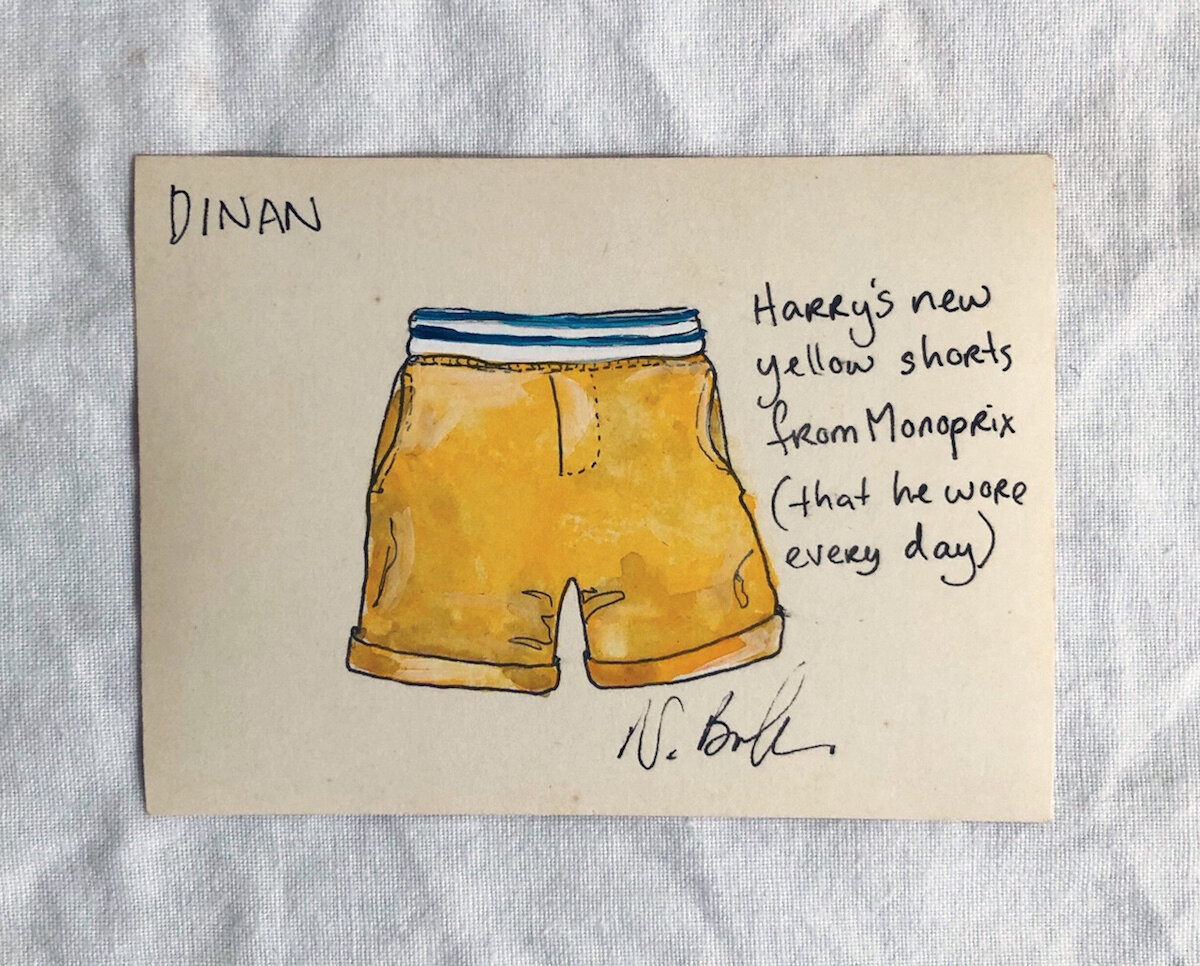

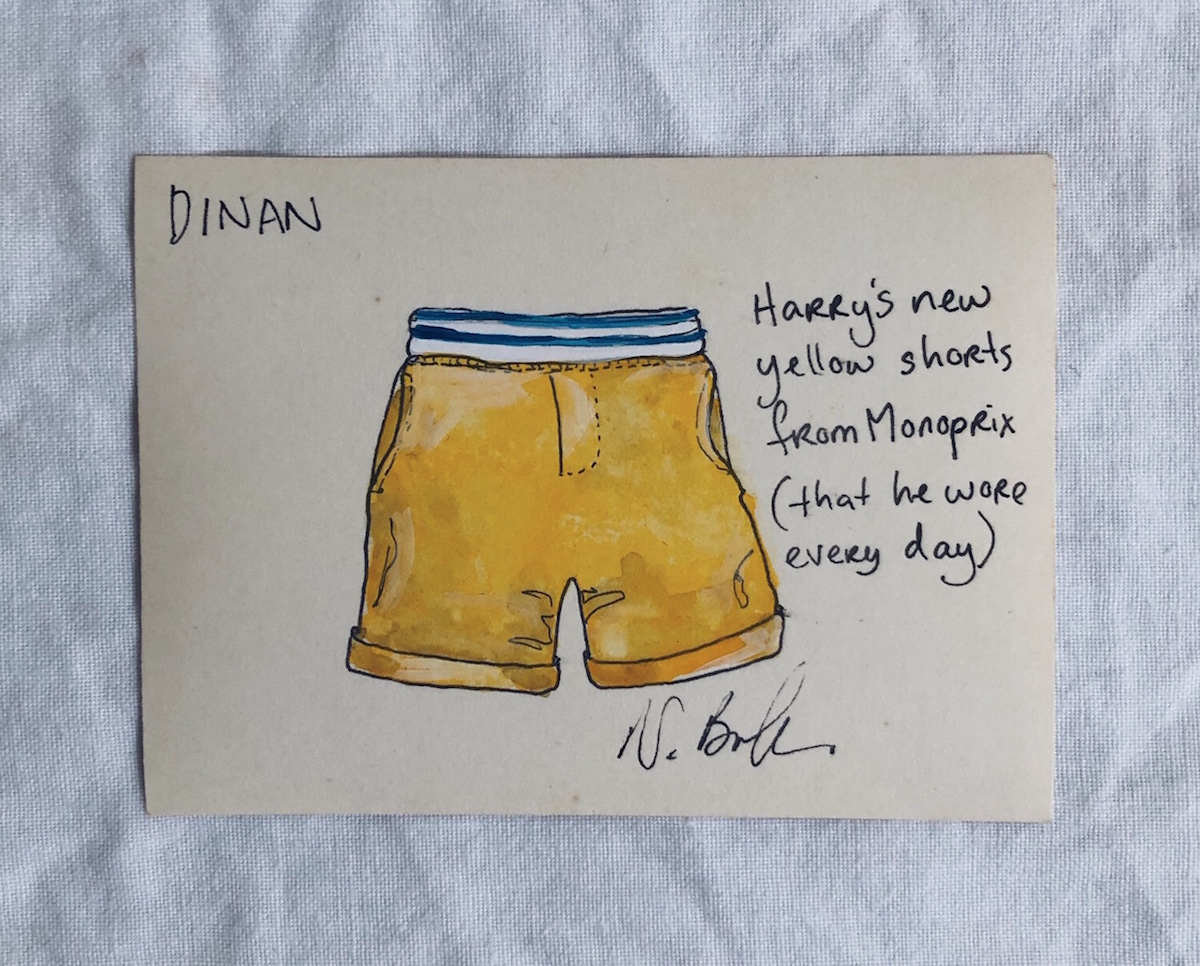

new yellow shorts

We arrived in France from the coldest month of winter in Australia, with very few summer clothes in the suitcase as the children had already grown out of theirs from six months earlier. While riding the carousel in the hot sun the day after our arrival, four-year-old Ralph found his jeans just - too - hot. I popped into the Monoprix and bought him these sweet yellow shorts, which he loved so much that he wore them nearly every day until the end of summer

maison bazille

There are several chocolatiers in Dinan, and we sampled them all! Our favourite was Maison Bazille on 10 Rue de l'Apport. Partly for the silky homemade chocolate (made on the premises) with all kinds of flavoured ganache, and partly for the macarons, but mostly because Anne, the proprietress, was just so lovely. She would welcome us with beaming smiles, and when we returned after three weeks in the UK, she gave the children cuddles and kisses. We would slow down every time we walked past, in order to catch her eye and wave

half-timbered houses

Dinan is famous in France for the half-timbered houses that line its streets. They are crooked and wonky, because when they were built (mostly the 14th and 15th Centuries) there was a tax on floor-space at the ground floor, so people built small at the base and increasingly spread out as they built up. (This particular house is now a restaurant, La Mere Pourcel on 3 Place des Merciers. I really wanted to eat there but it looked too fancy for a mum and two kids, so I’ll have to go next time!)

moules-frites marinieres

Ralph was gung-ho with the moules-frites from the very beginning, but Scout only discovered them during a visit to Mont Saint-Michel. It was a steaming hot day, and we sheltered from the sun in a restaurant for lunch. I’d ordered myself a bowl of moules-frites while the children had pizza, but Scout ended up stealing more than three-quarters of my mussels. We told the proprietress they were the best we’d ever tasted, and she smiled and shrugged, “c’est la saison” (it’s the season)

rampart towers

There are lovely little towers in the castle walls all the way around Dinan. This one is over one of the steep streets that lead between the hilltop part of the town, and the ancient river port. The children and I would walk along the ramparts on the way home from school, and stop to take in the view from the top of this tower

the padlock letterbox

The steep, cobblestoned rue du petit fort leads all the way down to the river at Dinan, and the whole way down the little street is lined with ancient and fascinating homes, shops and cafes. This door is almost at the bottom, and boasts the biggest padlock you have ever seen, which now does duty as a private letterbox

sea-birds

Dinan doesn’t feel like a seaside town. There is a river, to be sure, but it no longer dominates the landscape or trade, ever since the town moved up the hill and behind the castle walls for safety, many hundreds of years ago. But this is the west coast of Brittany, and the sea is still close enough that sea-birds call and circle in the morning, and wander through the streets hoping for scraps from tourists at lunch

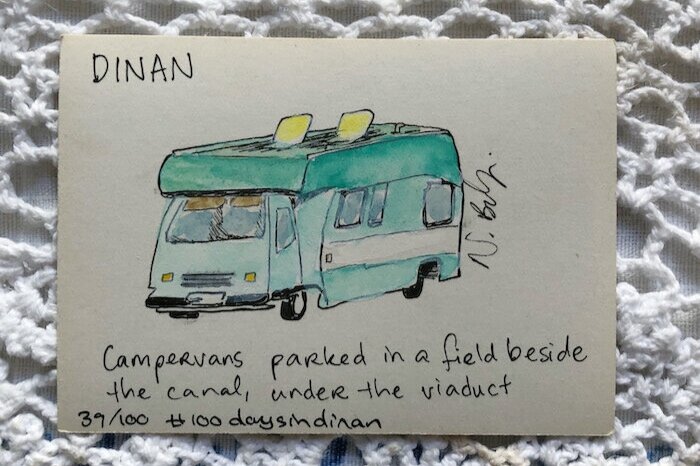

boats on the canal

The river Rance, by the time it gets to Dinan, is little more than a canal. The first week we arrived, we took a ride on a river-boat up the canal to the neighbouring town of Lehon, the children fascinated when we had to stop at a lock and wait for the water to rise. There was a path beside the canal where horses used to walk and pull the boats. Once, a family’s horse sadly died, so the captain’s wife had to ‘harness up’ and pull the boat herself. There are photos. In the summer, weekender boats like this one I’ve painted would chug past and we’d wave at them

birkenstock kilometres

The day before we left on our adventure, we took the children to the Birkenstock store in Melbourne and picked up a pair of sandals each. It was winter here in Australia, and they had long grown-out of their sandals from the previous summer. When we arrived in France, those sandals became synonymous with the new sense of adventure and resilience my children developed. From complaining about a two-block walk in Australia, they cheerfully walked 10+ kilometres every day in those sandals